Dan Eb, 2021 Nuffield Scholar, is based in Auckland. Dan runs Dirt Road Comms, established to support those building a more just food system. He is also the founder of Open Farms.

With one foot on a Kaipara farm and one in the city, Dan is well placed to talk about the importance of re-connecting urban kiwis with our land, food and farmers.

Awarded a Nuffield Scholarship in 2021, Dan completed his research on

The Home Paddock: A strategy for values-led redesign of the domestic food system.

Listen to Dan’s podcast or read the transcript below.

Bryan Gibson – Managing Editor of Farmer’s Weekly.

Kia Ora, you’ve joined the Ideas That Grow podcast, brought to you by Rural Leaders. In this series, we’ll be drawing on insights from innovative rural leaders to help plant ideas that grow so our regions can flourish. Ideas that Grow is presented in association with Farmers Weekly.

My name is Bryan Gibson. I’m the Managing Editor of Farmers Weekly and this week we are checking in with a recent Nuffield Scholar, Daniel Eb. How’s it going?

Daniel Eb – 2021 Nuffield Scholar, founder of Open Farms and marketing specialist.

Kia Ora. Very well, thanks.

BG: And where are you calling from?

DE: I’m calling from Auckland, but half the time you’ll find me at the family farm up in Kaipara.

BG: And is that where you grew up, in Kaipara?

Work fuelled by rural and urban perspectives.

DE: I mostly grew up in the city. I was very lucky to have a foot in both camps. We bought a farm when I was a teenager, and I would normally spend the weeks in the city. Then, either most weekends or every second weekend up at the farm. The older I’ve got, the more time I’ve been able to spend up there.

BG: I know a little bit about your work over the last few years. I mean, you’ve married those two aspects of your upbringing into a career, haven’t you?

DE: That’s exactly it. My mother’s been in public relations for a long time and my father’s a farmer. So I thought, you know what, let’s do agri-comms.

BG: You run Dirt Road Communications. Tell me a little bit about that.

DE: Dirt Road Communications is a purpose marketing agency. I’m selective of the people I work with. They need to be driving towards a shared mission of mine, which is a just and regenerative food system in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

I have the privilege of working with people like AgriWomen’s Development Trust, who are really focused on building capability amongst farmers. I work with local food system advocates as well. We’re looking more at systemic issues and big changes in food and farming. I support these people with digital marketing and brand positioning, helping them understand their value proposition, building big projects, that sort of thing.

Forging stronger connections to food and our farming system.

BG: That is in the same wheelhouse as your Nuffield Scholar Report, isn’t it?

DE: The report was an opportunity to slow down and look at the big picture as to the change these organisations are driving for. It was about articulating, well, what the future looks like when we achieve a food and farming system in New Zealand that benefits producers and every kiwi, because food is really important and it doesn’t just drive our economy, it drives our families, it drives our culture, and it drives our health.

The report was an opportunity to step back and paint a picture of what success could look like when we change that system.

BG: Yeah. It’s a criticism or a challenge often talked about in terms of our food production sector that it’s so good at certain things, but that it’s lost the connection to its own community, if you know what I mean? Because we export 95 % of all the food we produce. Therefore, all our food prices are driven by international market forces, like the price of cheese, which gets on everyone’s nerves. Is that something that you were looking to address?

DE: I think you’ve explained it really well. I like to tell stories to explain these big concepts. The thing I think about is, if you’re a kiwi mum living in, I don’t know, Auckland, Wellington, or Christchurch, 84 % of us live urban lives now, so you’re one of that big majority. You’re aware that in the background food and farming is important to New Zealand as an economic driver. But, the thing that you’re most worried about is, what are you feeding your child for dinner? Is it healthy? Is it nutritious? Has it been grown as sustainably as possible? Is it affordable?

As growers and producers, we’re really good at the production side of things, but that relationship is really important. That Kiwi mum’s kids are going to be the people that we want to recruit into food and farming later on. If they’ve got a broken relationship with food and farming, it’s going to be really difficult to encourage them into food and farming careers. That Kiwi mum’s a voter. She might end up voting for parties that want to be more restrictive on food production.

We’re seeing that now with all the regulation that’s coming through. There’s a missed opportunity that she’s not going to jump on social media or when she’s overseas, badmouth food and farming in New Zealand. There’s a missed opportunity to turn her into an advocate for what we’re doing because she has a broken relationship with food and farming or with farming.

How do we strengthen the connection to food and food production?

We can’t think about farming without thinking about its role in society, and this is now an urbanised society. Until we start building things to rebuild that connection and start taking that relationship seriously, we’re going to continue to see bad results. I think those three big areas; recruitment, social license, and the ability to tell a cool, authentic, proven story overseas.

BG: So how do you go about unpacking this, or solving this, or moving the dial on this problem in a Nuffield Scholar Report? Where did you start? How do you go about it?

DE: Slowly and painfully is probably the best description. The first place I went to was to take a really zoomed-out view, and think, how do we often think about food and farming, and how should we think about food and farming? We often think about it as a business and as an industry, but I feel that food and farming doesn’t necessarily belong just there. I think it should be thought about more as a public good.

Food and farming as a public good.

An example for public good is health care and education. These are sectors within our society that have a high degree of touch with everyday New Zealanders. There’s a whole lot of trust, like social license is almost unquestioned. No one questions whether we need education. It’s just there.

I’ve had the privilege of having a lot of time on farm, so I know that the farm can be a place of healing, it can be a place of learning, it could be a place of inspiration, it could be a place of health. In my eyes, farming has the ability to transcend just a mere industry: shoes, iPhones, socks, handbags, and actually sit in a public good space.

I think that reframe is really important because it opens up a lot of potential. Now you can start saying, well, how would we make farming more like education? Why is education such a trusted sector? It opens up more opportunities for things like funding, because now you can say, can we go to the Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Social Development, and the MPI together and do system change. Because it’s really good for society. So, you’re suddenly in a different ball game just from that mindset shift. So that was the first bit.

BG: And you’re not talking about, for example, if we look at education, a lot of the schools are run centrally. You’re talking more about a partnership in a way of looking at things. So farming businesses go, my bottom lines are met by making a profit on these animals that I raise, but also taking these things off in a social or environmental sense. Is that the idea?

DE: Yeah, that’s the starting place. Then you start to think about what concrete solutions would look like. Education might not be the best example in this instance. Healthcare is probably a better example. To me, healthcare is quite interesting because you effectively have two models that sit side by side. You’ve got a private health care model where people pay for service, and then you’ve got a public health care model. Interestingly, doctors flip between the two. You can have public doctors that operate privately and vice-versa.

Regardless of which system you play in, every doctor gets paid well. It’s a very respected role in society. To me, they’re solutions that mindset will prompt you into.

A relatively concrete solution that I could see is if there was an organisation set up to encourage farmers who are farming close to cities to transition to local food economies and local food business models. Whether that’s community supported agriculture or technology driven food distribution, like Happy Cow Milk, which is the Fonterra factory-in-a-box model. That has some government support because it would be required to reduce the amount that some consumers are paying for food and it could operate on something like a postcode system where, depending on your postcode, you pay a different amount for your food.

But alternatively, a farmer who’s further away from town would probably participate in the more status quo export model running through your processor and then selling our kai overseas. There’s no reason why those two things can’t sit well blended together. But by having that, some farmers incentivised to operate in that local system, you’re solving all these other big issues like social license, like recruitment, like people understanding where their food comes from, and also creating this really fertile ground to tell a really compelling international story about food security and how important kai is to New Zealanders, and this is how we treat it. You’re creating content and you’re building this overseas provenance story as well.

So, a lot of it really does sit within that reframe that, you know what, smart investment from industry and government into these public good food system models, particularly local, can net some massive results in the long-run.

Opening farms for a win-win.

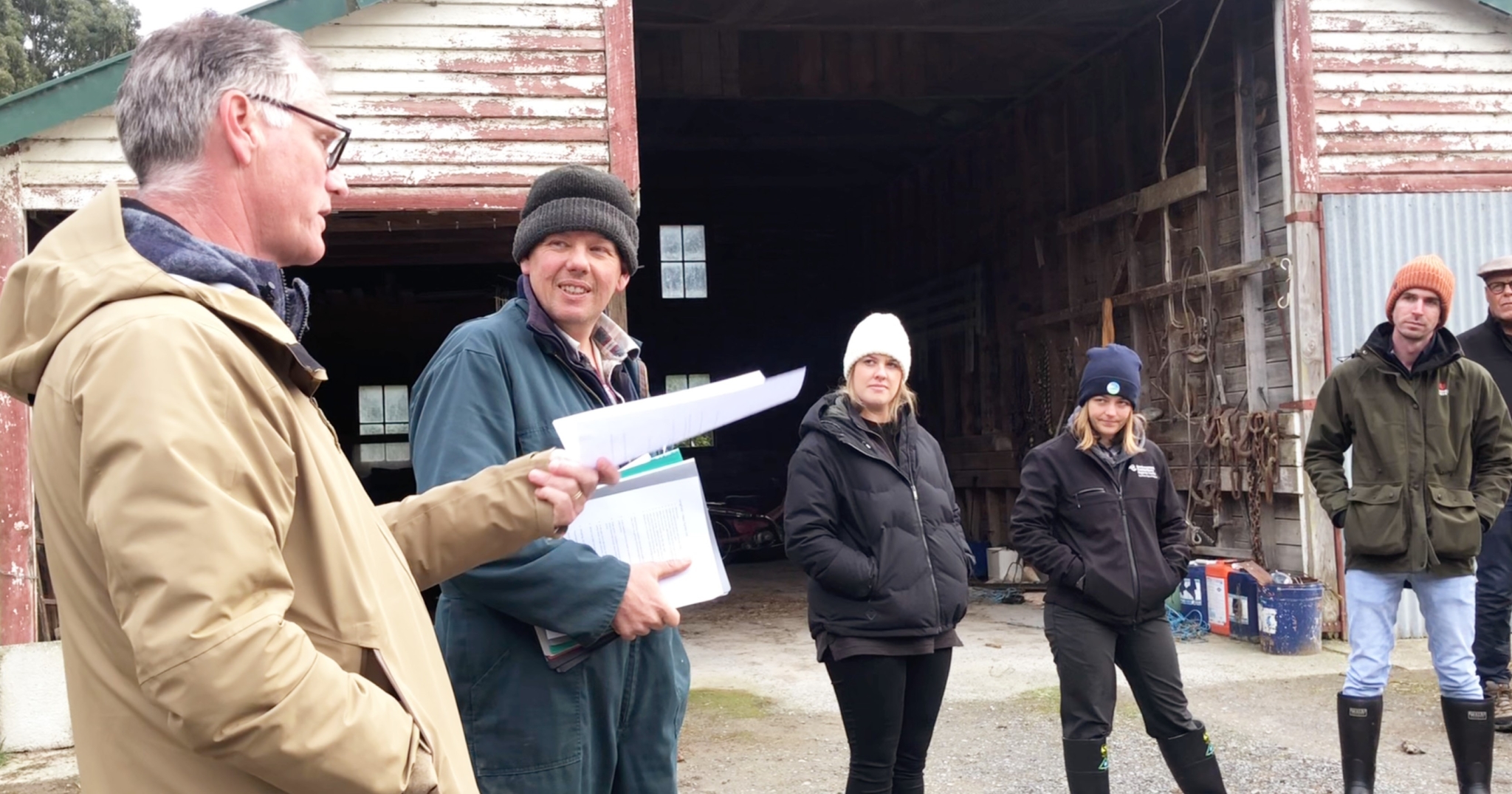

BG: I guess we should mention, since you’re the bright spark behind Open Farms, that programme was run on a lot of farms and most of them were relatively close to urban centres. That showed that there was appetite from both farmers and from the general public to come together and engage on this food journey.

DE: Exactly, and I think if we could build local food models that by design connect urban kiwis with the sources of at least some of their food production, then there’s an economic rationale to a farmer to host open days. Now there’s an economic rationale for a farmer to connect with a local school, and maybe there’s some financial incentives that go along with that. Suddenly, you’re breaking that barrier, that 60-minute barrier between city limits and where farming starts.

You start blurring that line and I think the blurring that line is really important if we’re going to solve some of these entrenched issues that urbanism has created over the last 50, 60 years. But we need new models to do that. We can’t just hope a couple of open farm days are going to do it. We actually have to do relatively large system change to design the outcomes that we want.

BG: What else did you find in your report that you think could help in this values driven food transition?

DE: I think it’s important to believe this change is already happening. This isn’t something we have to manufacture. This idea of citizen connected businesses or new business models; this stuff’s already happening organically. It’s about latching on to that. Instead of seeing that as a threat to the export talk, dominated, centralised system of food, we see that as a really supportive ancillary model that the two can gel well together. I do just want to reiterate that these two models aren’t in competition at all. Quite the opposite. I know when we talk about public good, it starts getting into the realm of politics and words like socialism get thrown around and stuff like that, I think that’s a side track.

At the end of the day, we’ve got to focus on the outcomes we actually want and be a bit ideologically agnostic. This is 2023, and we need every tool we’ve got on the table to fix some of these deeply entrenched problems. In terms of other stuff, I think there’s a whole lot of smart tactical plays that we can do to get us there as well.

The Nuffield Global Focus Programme and public good overseas.

These are things like social diversifications that we can layer on to farms. I’ve just come back from my Nuffield GFP travel, and one of the things that really stood out was a bunch of people in the Netherlands who are using their farms in partnership with local health care providers or local schools. These are financial business transactions and having kids come onto the farm regularly as a partnership with local schools. It’s becoming an education platform.

There was one farmer who had partnered with a local healthcare provider to bring kids with learning disabilities onto the farm. It was a collaboration between a healthcare provider, a learning disability specialist, and the farmer. They were all co-collaborating to create this programme for those kids. Now, the funder is the Ministry of either education or health care in that instance. But that diversification costs the farmer to build a hut to make sure they don’t get rained on and some time to build the system. But at the end of the day, that’s a revenue generating diversification that he’s layered onto his farm. That costs him very little and it’s returning him a good profit.

We’re desperate for these ways to eke out some more margin off our landscapes. I just think that these community connection diversifications are an unearthed gem. They cost very little to do. Yes, there’s some soft skills that are required, and there’d be some upskilling, and you’d have to get relatively comfortable with new people coming onto the farm too. But it’s a lot cheaper than putting in kiwifruit for example. Then you’re also running the risk of a bad harvest and all that stuff. There’s very little risk here.

I think in a time when traditional food production on our farms is becoming harder; pick a reason: government regulation, higher import costs, climate change, poor returns on global markets, this social diversification is just gold. I just don’t feel that enough farmers, particularly in those peri-urban areas, are seeing that. That’s what a large part of my work is, building projects that make it easy to move into this new citizen-connected farming model, which I think is going to be really valuable for farmers who are cash-strapped.

BG: Now, you mentioned your travels. That’s obviously a big part of the Nuffield. Any other highlights from your trips you abroad?

DE: Heaps. I’m trying to write up a bit of a reflections document now. It’s hard because I keep trying to add stuff in instead of taking stuff out. We had a great group. We went to Japan, then Israel, then the Netherlands, then Washington DC, and the Central Valley in California. To me, a highlight was seeing what the driving force behind agriculture in these different contexts was. We’d go to Israel where water infrastructure was at the scale and of the excellent standard that it is, not because of government policies or anything like that, but it was all done for security reasons. Security is the number one driver in Israel. So, agriculture is almost a by-product of security. That’s what happens when you fight three existential wars in the last 70 odd years.

Interestingly, the big driver in a place like Japan was tradition. They’ve actually inadvertently figured out through trial and error and population growth in a relatively restricted coastal plain, that they have to fuse agriculture and urban life together. Outside of downtown Tokyo, the landscape is a mix of residential business, rice paddies, vegetable gardens.

They don’t have a social license problem because their geography represents that breaking of the barriers and fusion of urban and rural and food production and the lifestyles that I’ve been talking about. The geography has pushed them into a space. It’s interesting to look at those places and think, Well, what’s our driving force? If we’re honest with ourselves, right now, it’s agribusiness. It’s an economic powerhouse. There’s nothing right or wrong with that. But to me, that feels very limited. I think there’s a lot we can explore and experiment on top of it as just an economic powerhouse.

I think food and farming can be a public good. Interestingly, I think our geography, this idea that we’re basically restricted as Kiwis to our urban centres, and there’s a whole lot of farmland in between, that’s a huge barrier. We’ve got to build little strings and break little gaps in that wall, particularly in our peri-urban areas, to get where we want to go. That being a society where people are really proud of food and farming, are healthy, and see food and farming not just as a viable career, but as a mission and a purpose for something that they want to do for the rest of their life.

I think that’s entirely achievable. We just got to build things to do it.

The Nuffield Scholarship experience.

BG: How have you found the Nuffield experience overall?

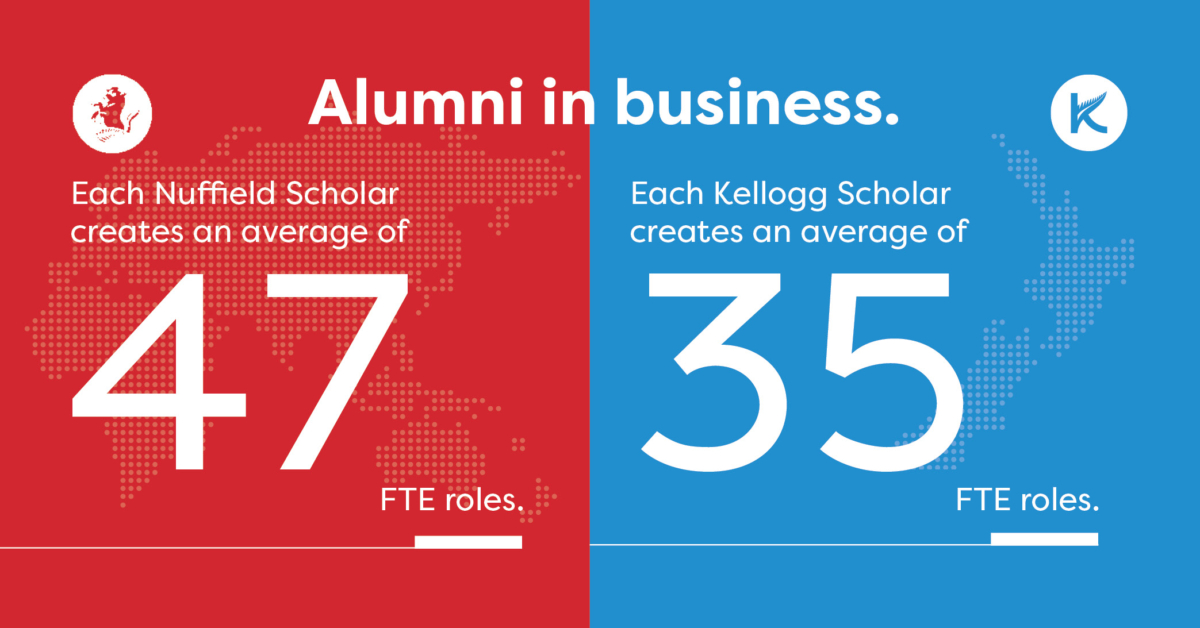

DE: Awesome. Honestly, I can’t recommend it highly enough. I think everyone’s experience is a little bit different. I think it can give you what you’re looking for, even if you don’t really know what that is. For me, it was time. It was a forced requirement to sit down and write out my manifesto, almost. These thoughts are running through my head. How are they all working together? What am I aiming for? And that was really valuable for me. It’s enabled me to articulate some of these things, which are pretty hard ideas to describe. And so Nuffield gave me time, whereas I can say that for a lot of my fellow scholars, Nuffield gave them experience, or some learning about themselves that they wouldn’t otherwise have got. For me, it was time.

BG: Thanks for listening to Ideas that Grow, a Rural Leaders podcast in partnership with Massey and Lincoln Universities, AGMARDT and Food HQ. This podcast was presented by Farmers Weekly.

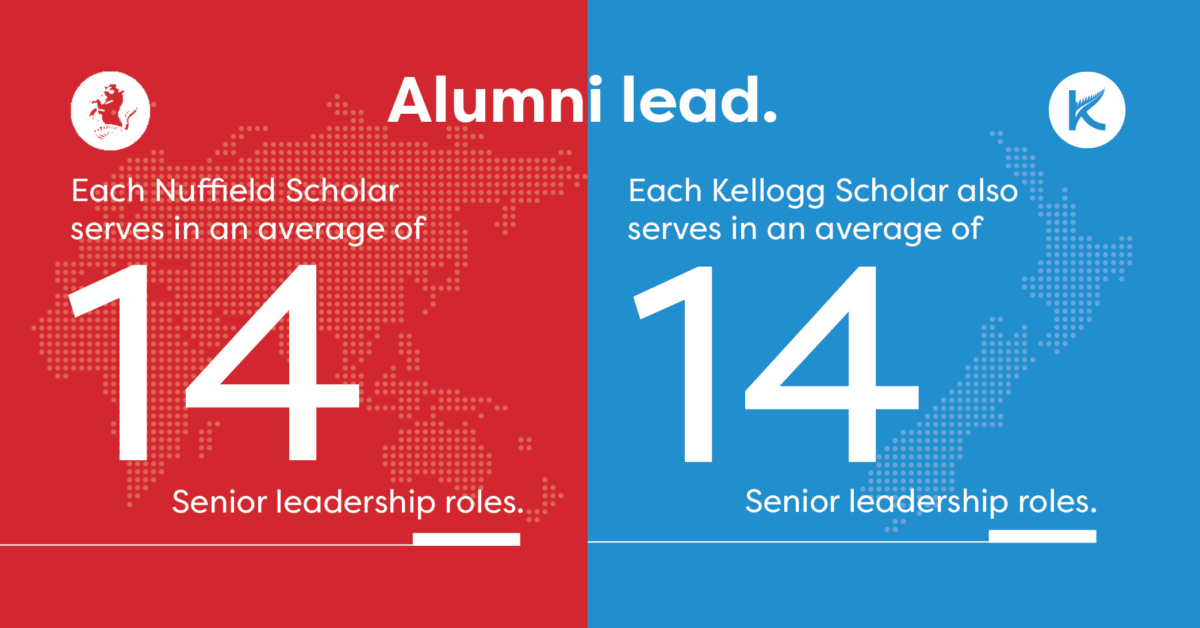

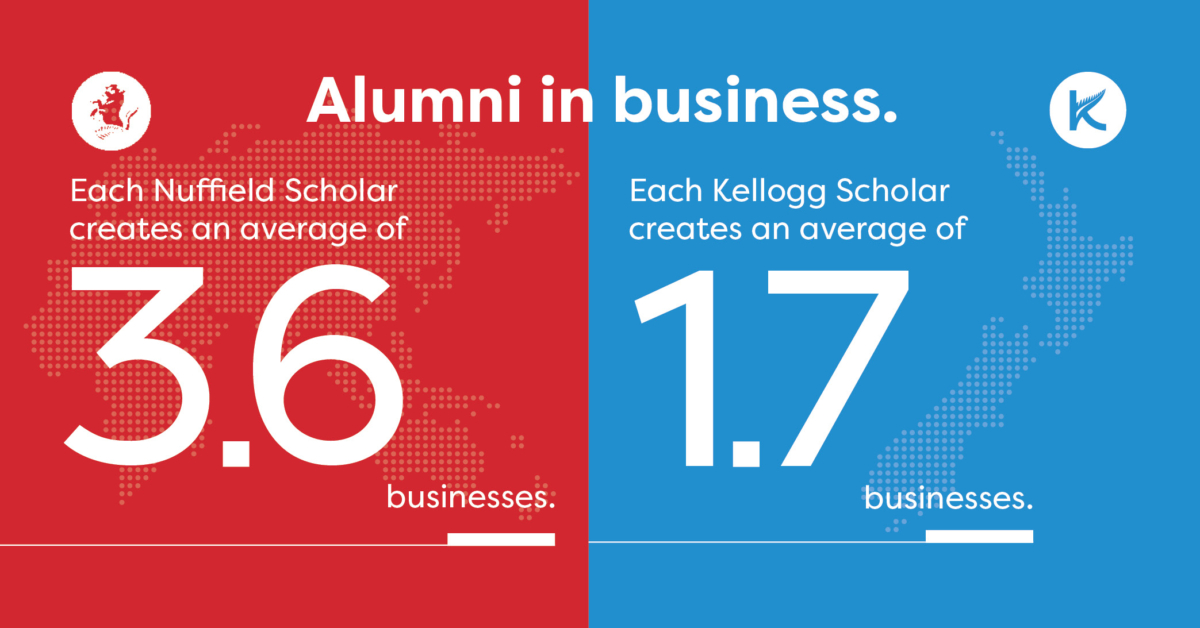

For more information on Rural Leaders, the Nuffield New Zealand Farming Scholarships, the Kellogg Rural Leadership Programme, or the Value Chain Innovation Programme, please visit ruralleaders.co.nz