The Mackenzie Charitable Foundation have initiated research alongside the New Zealand Rural Leadership Trust, in collaboration with Otago Business School and the Department of Economics, to investigate the contribution of Kellogg and Nuffield Alumni to Food and Fibre.

Research covering 72 years of Nuffield and 43 years of Kellogg Rural Scholarship.

The objective of the research has been to collect data measuring within-person gains in entrepreneurial leadership and capability-building that occurs because of the Kellogg and Nuffield programmes.

The first survey was conducted with the New Zealand Nuffield Alums (178 at the time of the survey – with 68 survey participants). Through this process, the Team learned several ways to refine the survey and then ran a similar survey with Kellogg Alums (960 at the time of the survey – with 234 survey participants).

Entrepreneurship is frequently measured as the proportion of people in self-employment. By that broad measure, the Study has found that rural entrepreneurship is very much alive and well among alums.

This latest Mackenzie Study report builds on the progress report from February 2022 and as such, offers a recalibration of some earlier published headline results.

The methods used to measure entrepreneurial leadership skills (ELS) draw on international peer-reviewed academic literature in experimental economics, psychology, and management science.

The Study measured real-world entrepreneurial achievements by counting new business starts, FTE jobs created, export revenues, and leadership roles. This contributes to the participant’s ELS profile.

Characteristics of the Nuffield and the Kellogg Scholar.

Nuffield Scholars are, on average, in their 40s. They are rigorously selected and undertake a self-guided international exploration of Food and Fibre challenges and opportunities.

The Nuffield Scholarship is runs over 15 months and includes at least 16 weeks of international travel.

Nuffield aims to develop the insight and foresight to keep New Zealand at the global forefront of Food and Fibre-producing nations. Leadership development is an outcome of each Scholar’s experiential journey rather than an output of the Programme.

By contrast, Kellogg Scholars are, on average, in their 30s. The Kellogg

The Programme is facilitated and runs over six months. Each programme can take up to 24 Scholars, meaning more Kellogg Scholars graduate than Nuffield Scholars. Leadership capabilities are a defined learning output of the Programme.

This is likely a first-of-its-kind cross-sectional study, designed to compare each participant at multiple time points and will give New Zealand’s Food and Fibre sector a world-leading insight into the art and science of building entrepreneurial capability.

Here are the headline results from the Study.

Nuffield.

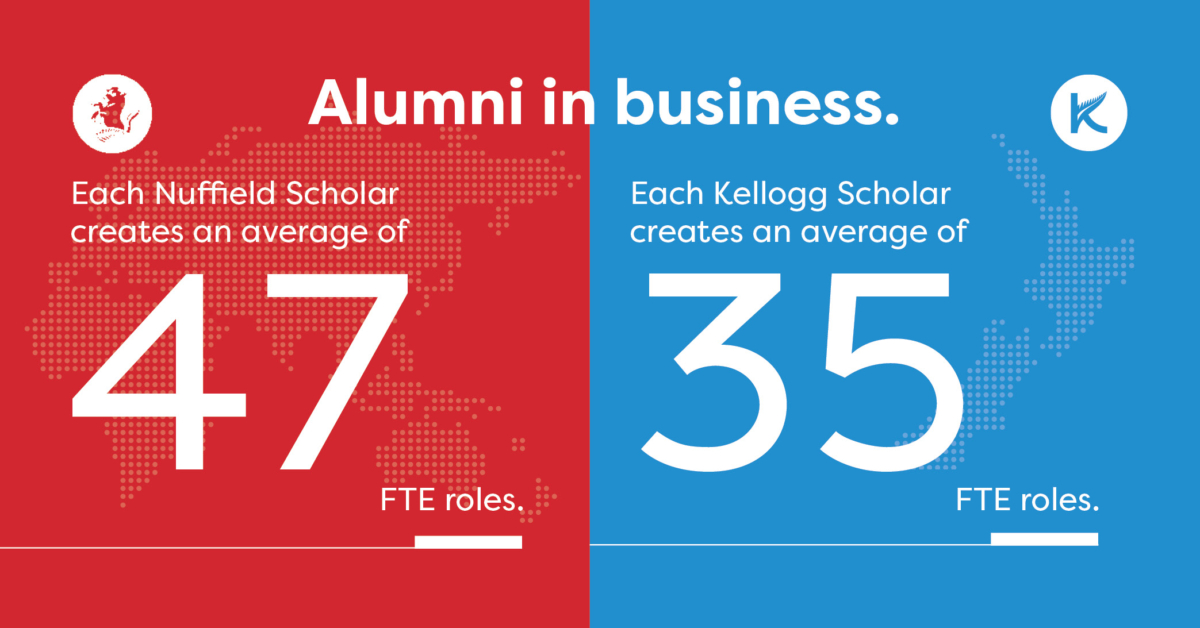

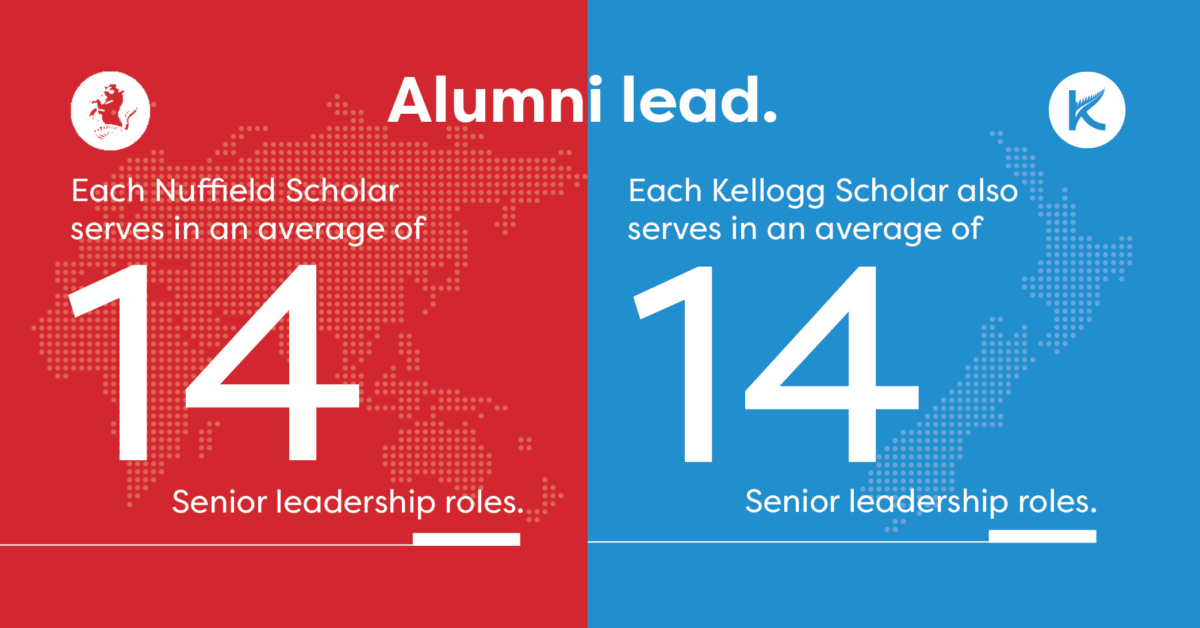

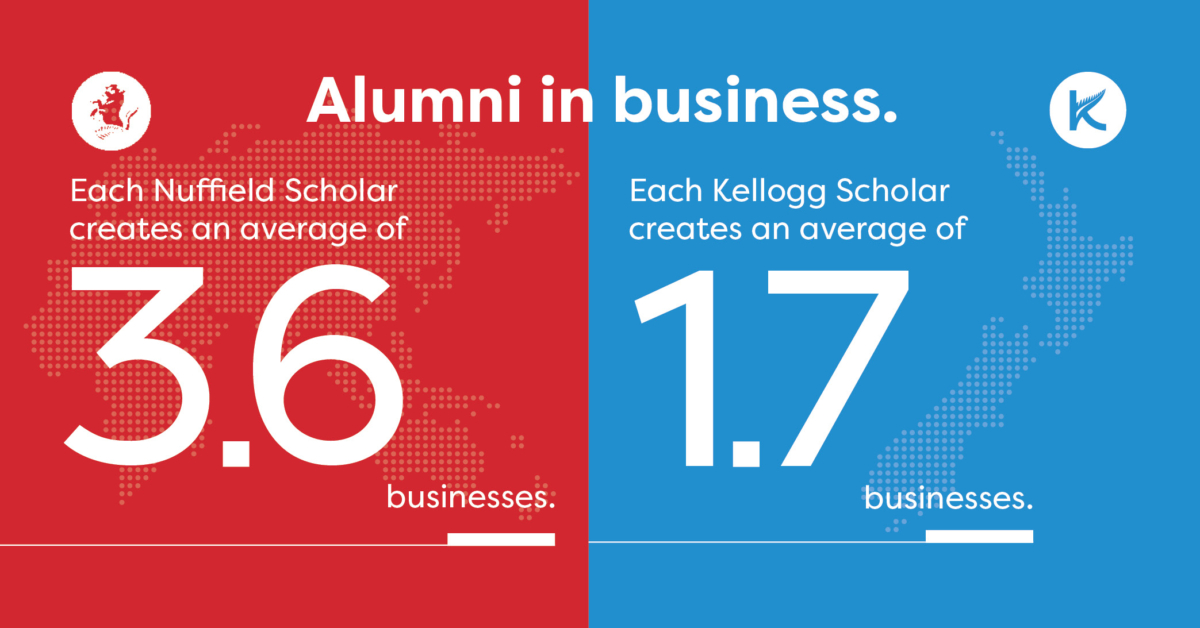

The average Nuffield alum has started 3.6 businesses, played a direct role in creating 47.0 FTE jobs, and served in 14.0 senior leadership roles.

Over 40% of Nuffield alums have served in government-appointed or elected leadership roles. At the time of survey, 178 Nuffield alums had collectively served in an estimated 2,488 leadership roles (other than government roles), played a direct role in creating an estimated 641 businesses, and 8,295 FTE roles.

Kellogg.

The average Kellogg alum has started 1.7 businesses, created 35.0 FTE jobs, and served in 14.0 senior leadership roles.

Approximately 26.9% of Kellogg alums have served in government-appointed or elected leadership roles. Since the inception of the New Zealand Kellogg Rural Leadership Programme, 960 Kellogg alums have collectively served in over 26,858 leadership roles (other than government roles), played a direct role in creating an estimated 1,632 businesses, and 33,600 FTE roles.

The collective Nuffield and Kellogg Alum’s results.

These collective results include the creation of an estimated 2,273 businesses, 41,895

jobs, and service in 29,347 leadership roles.

Just as importantly, both alum groups reported better personal outcomes after attending the programmes, including better well-being, expanded social networks, and higher earnings. This is an impressive contribution.

Both alum groups demonstrated economic, social, and environmental contributions to New Zealand’s Food and Fibre sector. One of the notable findings is the very high rate of self-employment compared to New Zealand as a whole (over 60% for Nuffield and Kellogg, compared to 7.5% nationally, 28% in the dairy industry, and 30% in the red meat and wool industry).

The Team have seen very few data sets in New Zealand with self-employed proportions this large.

Where to next for the Mackenzie Study?

The Mackenzie Study also includes foundational data for longitudinal research. The analysis of this is currently underway. The longitudinal study is focused on collection of before-after survey data for just the Kellogg Programme.

The intention is for this data collection to continue as future cohorts’ baseline and exit surveys are added. This, in order to achieve greater statistical precision and an ever-strengthening evidence base documenting gains in entrepreneurial leadership associated with participation in the Kellogg Programme.