Farmers Weekly Managing Editor Bryan Gibson speaks to Jen Corkran, Senior Animal Protein Analyst at Rabobank and a 2023 Kellogg Scholar.

Jen discusses her day job to provide red meat insights to clients and farmers. Jen also reveals what her Kellogg research tells us about trust, truth and the way farmers take on information.

Listen to Jen’s podcast here or read the transcript below.

Bryan Gibson – Managing Editor of Farmer’s Weekly.

Kia Ora, you’ve joined the Ideas That Grow podcast, brought to you by Rural Leaders. In this series, we’ll be drawing on insights from innovative rural leaders to help plant ideas that grow so our regions can flourish. Ideas that Grow is presented in association with Farmers Weekly.

Bryan Gibson, Managing Editor of Farmers Weekly.

You’re with Ideas That Grow, the Rural Leaders podcast. I’m Farmers Weekly Editor, Bryan Gibson, and with me today is Jen Corkran, a Kellogg Scholar. G’day Jen, how’s it going?

Jen Corkran, 2023 Kellogg Scholar, Senior Animal Protein Analyst at Rabobank.

Hi, Bryan. It’s good here. How are you?

BG: Yeah, pretty good, thanks. To get started, tell us a little bit about your background. Where are you from?

Foundations in rural Hawkes Bay.

JC: I grew up in rural Central Hawkes Bay, in a little town called Waipukarau. My mum was a teacher at a primary school there, Flemington School, so right in the heart of sheep and beef country in Hawkes Bay.

I grew up and went to primary school there and I think from that grew this really in-depth passion for the agriculture industry in New Zealand. Ever since I can remember, I wanted to be a farmer. So, I think that background set me up well for that.

BG: Did that follow through to higher education or your first jobs, that sort of thing?

JC: Yeah, it did. After high school, I went to Massey in Palmerston North and studied agricultural science down there for three years, which was good fun. From there, I went farming in mid-Canterbury for a couple of years on a big beef farm. This is early, mid-2000’s, before the dairy boom. There was still a lot of sheep and beef country down that way. Before this farm did end up converting to dairy, it was all flood-irrigated beef, and spent two years down there as stock manager, which was great fun, especially coming straight out of university and not actually growing up on a big farm.

We did have a lifestyle block there in the Hawkes Bay with 70 odd sheep and a few cattle. But this gave me that real, in-depth understanding of farming, and through the seasons, and the longer term understanding of what it takes.

From that, I got inspired to go back to uni to do some post-grad. I did an honors year in Pastoral Science and Sheep and Beef Farm Systems. After that, it was great coming back into that, having spent some time farming as well. Then after few years in the UK I moved back to New Zealand.

Senior Animal Protein Analyst, Rabobank Research Team.

BG: Yeah. And you’re with Rabobank right now. What do you do there?

JC: Yes. I’m the Senior Animal Protein Analyst in the Rabo Research Team. So our job in Rabo Research is pretty much to provide insights and understanding around what’s happening in the markets in that global picture. My area in animal protein is red meat, for New Zealand, so sheep and beef. We cover all the commodities. In the team I sit in, we’ve got dairy in New Zealand, and sheep, beef, and then we’ve got a whole bunch of other Rabo Research analysts who sit out of Sydney and Australia and cover off a whole bunch of other stuff.

So great to be part of a global team as well. There are analysts all around the world for Rabobank. We’ve got real global reach to find out what’s going on in other markets, what’s driving some of the things that we’re seeing down here in New Zealand. We provide that insight to clients and farmers in New Zealand, arming people with good information so they can make the best decisions for their farming businesses.

BG: We enjoy getting your guys insights across our desks here at the Farmers Weekly. They usually turn into good stories. Now, talking today about your Kellogg Scholarship Programme. Tell us a little bit about what you decided to study?

Kellogg Programme research on pastoral farmer learning preferences.

Image: Jen Corkran speaking in Rabobank site at the Wanaka A&P, March 2024. (Rabobank’s Scott Levings in blue looking on).

JC: My research for Kellogg was on farmer learning preferences, pastoral farmers, to be specific. I was with Barenbrug New Zealand for over 10 years before starting with Rabobank. So, when I did Kellogg last year, I was still with Barenbrug. As a Pastoral Seed Company, they really wanted to understand how farmers are learning and getting information; pastoral is our bread and butter here in New Zealand. We turn grass into saleable protein.

How our farmers learning anything to do with harvesting homegrown feed? So, we know that the most profitable farm systems in New Zealand harvest the highest amounts of homegrown feed because it’s the cheapest form of feed, and they turn that into milk or meat. So, I guess Barenberg is a business, and I really was quite passionate about this topic, too, because at the time, I was in a pasture specialist role around helping farmers get the best from their grass and crops. How do they learn? How do they prefer to get information? And from that, what do they do with it, basically?

It was essentially more of a social science topic in terms of adult learning preferences. And some interesting results came out of that. It was a challenging project, but certainly understanding people and what makes them work is part of what we all do every day, too. So, yeah, it was great.

BG: That issue of tech and knowledge transfer through to the boots on the ground in the farming sector is one that has had lots of people scratching their heads over time. What were the key findings? How do farmers like to learn things.

What the Kellogg research revealed.

JC: So, there’s a lot to it. I had to go right back to the start to understand some of what’s already been done in that space. So, a big literature review in terms of what do we already know about how our farmers learn? You can look overseas, but really we’re quite a unique here in New Zealand, and we want to know how we, as more outdoor feed systems, are doing things.

So, yes, a big literature review in terms of what’s already been done. There’s a lot of work that’s been done, but it’s quite complex. But the real interesting findings came with actual farmer interviews. Just talking to farmers all around New Zealand, both in the dry stock, red meat sector, and also dairy, cropping, arable, whatever it might be, to find out how they learn. What we found was these two broad pillars, when it comes to learning, there’s a purely learning aspect, and then there’s a social aspect. They’re both equally as important as each other. And when it comes to learning, there’s information. People need to know what it is that they’re after. They also have to make a decision.

But before all of that, they need to be aware of what the thing might be. So for example, a new type of crop that might suit a certain area of New Zealand, say a summer crop where it’s summer dry, and this thing’s going to provide protein over that time. Before a farmer is even going to think about putting this new crop in, they’re going to be aware that it even exists and then understand how it works. What overlies that is understanding it through information, so whether it’s data or science or trials or your neighbour tried it, to make a decision to whether it will work for them. So that’s understanding their own farm business and seeing if it’s relevant.

Relevance is hugely important. But what overlays basically everything is this social aspect around trust and trusting the information that they’re getting is both true and relevant to them. Also, I guess, having a yarn about it with other people, as farmers in New Zealand, like to do. So this whole networks, trusted networks, trust is really key to farmer learning.

The other big one, I guess, that overlays the learning aspect is relevance to farm system. So, a dairy farmer is not going to necessarily be selling the same pasture and using it in the same way as a sheep farmer who struggles with more dry or harder conditions or in different soil types. They were the key pillars, I suppose. Obviously, in interviews with farmers, it was just so interesting to see all the themes lining up – networks and trust, those two words came up-time and time again.

Building trust takes time.

BG: Obviously, trust is the key. It doesn’t really matter where that trust lies. It could be different for different farmers, say, friends or colleagues or catchment group members, or it could be the seed rep or someone else. As long as there’s that relationship there, is that the thing that drives any evolution?

JC: Yeah, 100 %. What I basically did with the interviews is get a transcript and look for themes – a thematic analysis of themes. Some of the keywords that kept coming up were ‘trust takes time’, and trust doesn’t have to be for a person necessarily. It could be for a brand or a company or a business or a thing. But building trust takes time and has to be something that’s proven. I think a lot of farmers, and it’s something we hear as people in the industry all the time, you can’t just assume that you meet someone and then they’re going to trust what you’ve got to say. You have to earn it. And ‘earning trust’, I think, was one of the key things that kept coming up again and again. A business can become a trusted business within the inc of New Zealand also, and so can individual people.

Often, farmers said, they might have an agronomist who works for X company, and it’s the agronomist that they trust, and they’re going to follow that agronomist wherever they go through their career or their seed rep, or whoever it might be. Or it might be that they trust this particular brand, and they’re going to follow that. It could be whatever, but it has to be earned. I guess, backed up by some positive that they’re seeing. A lot of us work in the same way. We want to trust what we’re doing, and it becomes easier to make a decision if you trust that it is a safe one, I suppose.

BG: Farm owners hold a lot of the purse strings in terms of the wider industry, so they’ve got a lot of people coming down the driveway trying to sell them the newest and best thing. They do have that detector to go, ‘well, is this going to work for me. Or is this just someone trying to sell me something new and unproven or a one-size-fits-all approach?’ They really need to have that filter on, don’t they?

Trust in rural New Zealand.

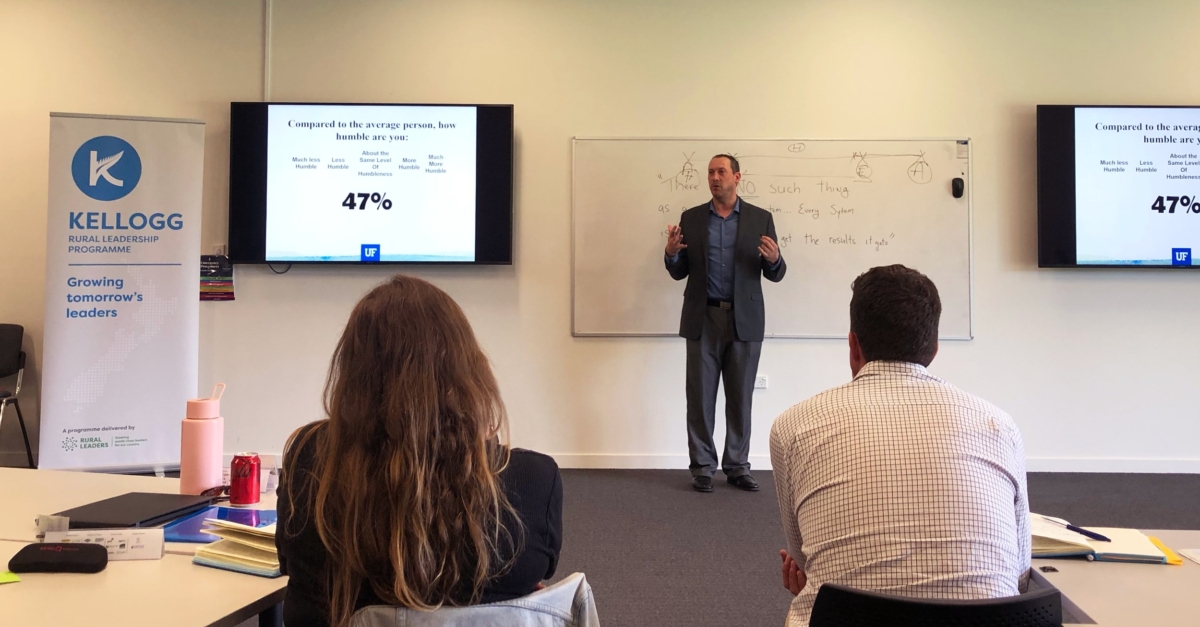

JC: It was really interesting, because with the Kellogg Programme itself, we do the research project as one part of it. And then the other part of it that’s within the actual course itself in the in-person phases, is learning for all of us on the course. A lot of this was around critical thinking. How do you get to a place of trust, asking the right questions, critically thinking about things so that you are asking the right curious questions to find out if something is true or not.

We live in an age where there’s so much information out there. You type something into a little square on your computer screen, and you can come up with scrolls of information. But what’s actually true and what’s not, and how do we trust it? So, it was really interesting. Some of the stuff we learned about misinformation and disinformation and critical thinking on Kellogg really paralleled a lot with what the farmers were naturally saying and doing.

Some of the most experienced business people are farmers, right? They have to be across so many different things. And so for me, doing a leadership course and seeing it tie in naturally with these amazing farmers around New Zealand was really cool.

They naturally have this ‘right, can I trust you or can I not?’ And a lot of them said, it sounds negative, but they didn’t mean it in a negative way. I’ll always start from a place of distrust trust and then move to trust. It’s not necessarily that you’re going to have trust straight away. So good thing to think about, I guess, for anyone dealing in rural industries in New Zealand.

The Kellogg experience.

BG: Yeah, for sure. How was your experience going through the Kellogg Programme?

JC: It was great, Bryan. You have six months, basically, where you have this tight knit group of anywhere between 18 and 24 people. There was 23 people on our course, cohort 50, we were last year. You get really close to these people. You spend the first 10 days down at Lincoln together all day, every day, learning about leadership and learning about yourself.

You’re on this journey together and so those networks that you make with the people in your cohort, you can’t really put any value on it because it’s golden. Because you’re doing the journey together, you’re in this challenging but stimulating environment. It was really, really great. And that network is for life now with those people.

Outside of the people that you’re doing your Kellogg with, I think for me, it was the leaders that were put in front of us. Seeing the characteristics that they had was really inspiring. They’re optimistic, a lot of them, there’s a lot of humility there. They’re curious, they ask questions, they’re open-minded. These are the ones that stood out to me as the most natural leaders.

They’ve obviously got all of these learnings along the way that have helped them get to this point that seems magical. You can see things in yourself that you maybe already have or that you need to work on because you’re just getting this exposure to these things that you wouldn’t necessarily get in that six month period.

Critical thinking, being curious, asking questions, keeping an open mind. There’s these themes that keep coming up over and over again. You see places for your own growth too. You see places where you’ve had challenging situations and you realise why, perhaps. So, In terms of leadership, there’s a heap of learning. In terms of that bigger picture thinking, where this tiny little export nation sitting in the South Pacific Sea, selling produce to the world, but we are affected globally by a lot of what goes on.

For me, very much in that pastoral science space at the time, it opened my mind up to this bigger picture way of thinking, which was my big learning. I did my Kellogg last year in my mid-30s. A great time to do it because I’d had a bit of life experience, a bit of career experience, but still you realise how much you’ve got to go and do. So, it was really good. Yeah, loved it.

BG: Awesome. And what’s the plan for you? Just still sinking your teeth into global protein markets, that thing?

JC: Yeah, that’s correct. Kellogg did open my mind to other opportunities and started with Rabo at the end of last year. So very much in that getting into the role space, what’s driving global protein consumption. We’re going through a challenging time right now in the red meat sector with meat prices, especially. There’s a number of reasons for that. What is the light at the end of the tunnel? When might we see it? So no, it’s really good, and I certainly, leapt right into that big picture thinking, which is great.

BG: Thanks for listening to Ideas that Grow, a Rural Leaders podcast in partnership with Massey and Lincoln Universities, AGMARDT, and FoodHQ. This podcast was presented by Farmers Weekly. For more information on Rural Leaders, the Nuffield New Zealand Farming Scholarships, or the Kellogg Rural Leadership Programme, please visit, ruralleaders.co.nz

For more information on Rural Leaders, the Nuffield New Zealand Farming Scholarships, the Kellogg Rural Leadership Programme, the Engage Programme, or the Value Chain Innovation Programme, please visit ruralleaders.co.nz