A fracturing social licence to farm.

Recruitment.

An authentic provenance story.

These are our sector’s most entrenched challenges.

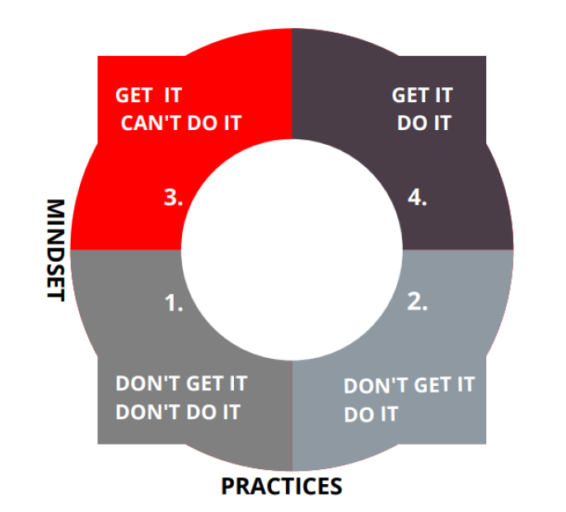

At their roots, they are about culture, values and perception.

They are homegrown, non-market problems confronting a sector that has optimised to win in the global marketplace. We can’t rely on our traditional strengths to produce, R&D or market our way out of them.

There is a tacit acceptance that the way forward is to shift from designing for volume and market value, to systems that also include social and environmental values.

To support that transition, this report imagines what a values-led food & farming system in Aotearoa New Zealand might look like. It’s built around an analogy, what if food & farming was more like healthcare and education – a public good. The analogy helps us to compare systems designed to sell to consumers, with those designed to more fully meet the needs of people. It helps us to see the challenges in values-led systems (like complexity, stakeholder collaboration and empathetic design) and their benefits (like trust, engagement and local prosperity).

In addition to the public good analogy, this report looks to examples in Kaupapa Māori, proposes a ‘cheat sheet’ for values-led innovation and explores five forms of values-led food & farming operating at the

edges of the sector.

It concludes with something concrete. A strategy for values-led redesign of the domestic market focussed on scaling local food & farming economies.

It’s a strategy to realise the untapped value in our domestic food system – our home paddock. It calls for enabling some farmers to look inwards and participate directly in their town’s local food economy.

It’s about designing around our values and practices that Kiwis increasingly want to engage with – like connecting to nature, learning & healing on farms or farming-based sustainability solutions. It proposes a

framework for action on food insecurity and health, two fundamental barriers to developing the ‘food & farming culture’ we need to rebuild social licence, recruit Kiwis and tell a provenance story to the world.

At its core, this is a strategy for building meaningful, everyday touchpoints with urban New Zealanders.

Because values matter across every kitchen table, community hall and boardroom – this report concludes by covering the potential roles of each sector player in a values-led domestic system.

We’re a trading nation, and we’re good at it. But we need to front-up to the fact that under the current export-dominated model, Kiwis feel increasingly disconnected from food & farming.

To meet these entrenched social challenges, we need to have the courage to do things differently – to lean into our values and redesign our home paddock, for local food & farming economies to thrive.

Here’s how.

Keywords for Search: Daniel Eb