Te Tiriti o Waitangi as a Founding document

The research report is committed to being responsive to Māori as Tangata Whenua and recognises the Tiriti o Waitangi as Aotearoa New Zealand’s founding document. The principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi as articulated by the Waitangi Tribunal, and the New Zealand Courts provides a framework for how we are to fulfil our obligations under the Te Tiriti daily.

More recently as outlined by the Ministry of Health, in 2019, “The Hauora Report” 1articulated five principles for primary care that are applicable to not only the wider health care system, but also to any person, organisation or Crown Agency working with Māori in our communities.

These principles are articulated as:

- Tino Rangatiratanga: The guarantee of tino rangatiratanga, which provides for Māori self-determination and mana Motuhake in the design, deliver and monitoring of community services.

- Equity: The principle of equity, which requires the Crown to commit to achieving equitable outcomes for Māori. This is achieved though breaking down barriers and enabling equity of access to ensure quality of outcomes.

- Active protection: The principle of active protection, which requires the Crown to act, to the fullest extent practicable to achieve equitable outcomes for Māori. This includes that it, its agents, and its Treaty partner are well informed on the extent and nature of both Māori wellbeing outcomes and efforts to achieve Māori wellbeing equity.

- Options: The principle of options which requires the Crown to provide for and properly resource kaupapa Māori services such as Ka Tipu Ka Ora. Also, the Crown is obliged to ensure that all services are provided in a culturally appropriate manner that recognises and supports the expression of Te Ao Māori models of service delivery.

- Partnership: The principle of Partnership which requires the Crown and Māori to work in partnership in the governance, design, delivery, and monitoring of community services. This includes enabling Māori to express tino rangatiratanga over participation in governance, design, delivery, and monitoring of community services.

For this research project and to understand the importance for Māori, it was important for me as the writer to enable the principles to guide my mahi.

It was also important to provide community level and grassroots level insights and intelligence to enable communities to partner on the development of services to create positive impacts for people throughout the community.

These services should focus on addressing equity of access to services in a manner that is consistent with tino rangatiratanga, active protection in the co-design, provide options to ensure culturally appropriate services and developed through a solutions focussed community led partnership approach with the Treaty always at the forefront.

Executive Summary

Everyone should have access to affordable, healthy food. However, across Aotearoa New Zealand a rapidly growing number of people are experiencing severe food insecurity – which means that they don’t know where their next meal is coming from, or if it will be nutritious enough to lead a healthy, active life.

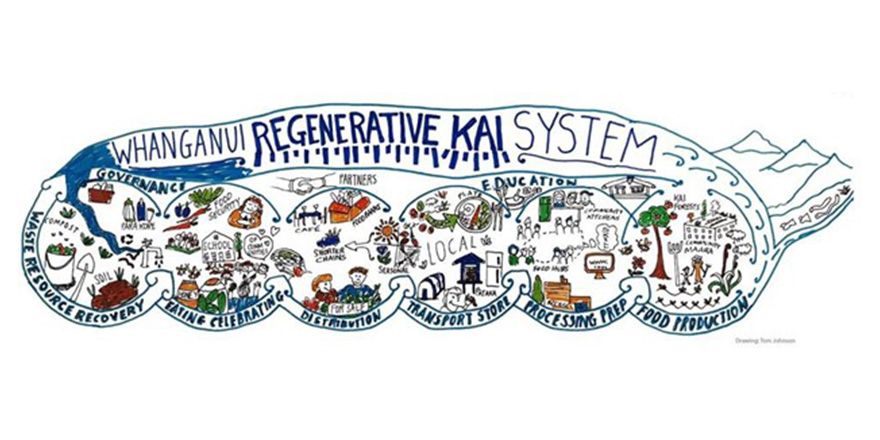

This research report will focus on answering the question of; How everyone, through a kaupapa Māori lens can move toward Sustainable Food Systems which are regenerative and resilient; prioritise locally grown and affordable kai; and uphold mātauranga (indigenous knowledge), kaitiakitanga (guardianship) and rangatiratanga (leadership) within this system.

This research also aims to help develop and establish sustainable local food systems, so all individuals and whānau have access to good food to improve community health and wellbeing; where “sustainable local food system” is a collaborative network that integrates sustainable food production, processing, distribution, consumption, and waste management to enhance the environmental, economic, and social health of a place, ensuring food security and nutrition.

This research supports the vision that everyone in Aotearoa New Zealand should be able to access good food at all times; where “good food” is food and beverages that are affordable, nourishing, appetising, sustainable, locally produced and culturally appropriate.

Key Findings

- Kai (food) is all about whakapapa (genealogy). It is the great connector that joins us to our tupuna (ancestors), our mokopuna (descendants), our whānau (families), te taiao (environment), and each other. Through kai we are connected to the plants, the animals, the waterways, the oceans, the forests, and the atua (deities). The recipes of our ancestors get pulled out in modern kitchens, linking us across time and bringing us together around the table to love and learn.

- Kai is central to Māori concepts of wellness and for generations it has brought whānau, hapū and iwi together. Kai is medicinal. When it is nutritionally dense and healthy, it feeds and heals our body and mind. When it is grown by our people, in our place, it feeds and heals our spirit. When it is prepared and eaten together, full of love, it feeds and heals our families and communities.

- Kai is the glue that holds so many of our communities together, and it is the sustenance that keeps our people well in body, mind, and spirit. However, for most people today our food system is not medicinal. Our current food system negatively affects our physical wellbeing, mental health, and community resilience. At the same time, the food system is causing environmental damage and degrading mana atua (spiritual integrity).

- Māori have solutions to regenerative and resilient food systems based on Mātauranga Māori.

- Many suburbs in Whanganui are food swamps and/or food deserts. This means residents and their population have good access to bad food and bad access to good food.

- Individuals and whānau in Whanganui are suffering from diet-related chronic diseases.

- One in five deaths can be associated with a bad diet. The leading diseases associated with diet-related deaths in New Zealand are coronary heart disease, stroke, colon, and rectum cancer.

- Those who live with diet-related diseases are more likely to experience poorer mental, social, and educational outcomes.

- Community, non-governmental, and non-profit organisations deliver several initiatives tackling the food system, particularly around urban production, and food environments. However, many of these initiatives face obstacles including policy constraints, funding constraints and lack of influence or access to decision-makers.

- There are also significant and complex underlying systemic issues that cannot be addressed by the community alone e.g., loss of productive land, unsustainable business practices, waste reduction, regulations that can lead to commercial interests favoured over community wellbeing, fragmented approaches to addressing the food system e.g., multiple stakeholders with shared interests working independently.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has seen growing discussion around the critical resource of food. And while New Zealand has an abundance of food produced from its land and seas, like many nations it still struggles with food security within its communities. The lockdown period had highlighted the need for resilient local food systems that can deliver food security and food sovereignty back to our communities.