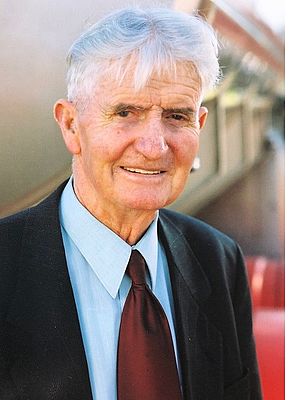

As well as a Nuffield Scholar, he was Federated Farmers National Dairy Chair, West Coast Provincial President and served for 48 years as a director on the Buller Valley, Karamea and Westland Dairy Companies.

A keen sports follower and marathon runner, Mr O’Connor was an active member of the West Coast Rural Support Trust even in his later life.

"If you’re a Coaster you’ll really appreciate the challenges there is farming near the mighty Buller River. Mr O’Connor epitomised the true West Coaster spirit through his determination and resilience to withstand the local climatic extremities. He also valiantly battled the scourge of TB in cattle and served on the RAHC – Tb Free as it is now called.

The West Coast farming community has lost one it its biggest battlers – he will be sorely missed," reflected Katie Milne, President of Federated Farmers.

West Coast dairy farmer and close friend Ian Robb, remembers Mr O’Connor’s engaging sense of humour and strong moral values.

"John had a kind, wonderful personality, he could relate to most people and the trials and tribulations they faced as farmers. He would always back the underdog and would seek out those doing it tough, and this was before the days of the Rural Support Trusts.

As his name goes, he definitely had that Irish charm. He was also a great orator and was adept at getting his point of view over in difficult conversations without offending anyone."

In his seventies, Mr O’Connor was so formidable and respected, he was still being re-elected to the Westland Dairy Companies when up against strong candidates.

"He didn’t always agree for example with the merging of the Coast’s dairy companies, but he soon got on with it, because he wanted farmers to succeed collectively," said Mr Robb.

Mr O’Connor is survived by his wife of 62 years, Del, six children and 20 grandchildren.

2018

Global Focus Programme – Kate Scott 2018

BRAZIL GFP 2018

10 Nuffield Scholars, 6 Weeks, 5 Countries, 23 Flights, 78 Visits & Meetings

After a whirlwind start to “Nuffield 18” and having survived the Contemporary Scholars Conference in the Netherlands, it was time to set out on my GFP – by all previous accounts the sort of trip that legends are made from!

Our group was known as the Brazil group, who would be travelling to Ireland, the USA, Mexico, Brazil and New Zealand. The first stop on our GFP was Ireland. Despite it being a little on the snowy side for our arrival into Dublin late on the Sunday night following St Patricks day (whether that was by bad luck or design is another debate), it was great to finally be on the road for the start of our six-week journey.

It is also fair to say that despite the quiet excitement there was also some apprehension amongst the group, and our ability to survive the next few weeks together in such close quarters.

Ireland

During our trip through Ireland we travelled from Dublin, through to Kilkenny, onto Tipperary, Kilarney, Ballybunion, and back to Dublin in the space of a week. We saw beef farms, dairy farms, pig farms and equine farms. We met dairy companies, organic orchardists, cropping farmers, research scientists and Nuffield Scholars, and throughout I was struck by how positive those involved in Irish Agriculture were, especially on the back of what many were calling the wettest spring in history.

The opportunities in Ireland, particularly in the dairy sector are in my view significant, especially in terms of their ability to continue to improve efficiency and productivity. In recent years it would seem that this is being driven by the removal of milk quotas. A simple example during our visit with Teagasc (Irish equivalent of Ag Research) is the more recent development and focus on herd production and the introduction of herd testing, which is still not widespread in Ireland, however over the past 18 years since the economic breeding index program was developed, Irish dairy farmers have started to see the improvement in productivity of their animals, which they expect will continue to be taken up by more farmers.

It has also been interesting to gain an insight into the fact that as a general rule the Irish do not have a great exposure to debt within their farming enterprises. Many are not prepared to utilise debt for expansion, something which I have observed as being largely borne out of the fact that farms are not generally brought and sold externally and are usually passed to the eldest son, and that any development is funded out of cashflow. This was certainly a contrast to the way that farming growth is financed in New Zealand, and was something I saw as a significant difference between New Zealand and Ireland.

It will be interesting to see over the coming years whether there is any change to the way in which they fund development given the expected growth within the Irish dairy sector. One thing that become apparent to me when travelling through Ireland was that many Irish farmers have been exposed to the negative press that farming in New Zealand has been receiving. In particular with respect to water quality and the environment, and most, if not all, were of the opinion that farmers in Ireland were not held in the same “low” regard by their public.

This was something that was discussed in depth when I had the opportunity to participate in a Nuffield Ireland debate on “Fake News & Agriculture”.

On the flip side however, it seems that the animal welfare debate and the “rise of militant veganism” was something that was causing concern to the agriculture sector in Ireland, that I am not seeing to the same extent here in New Zealand.

“That frog was right…it isn’t easy being green” – Anon

United States

The second phase of our trip was the USA. Here we had the opportunity to meet up with the Chile and Africa GFP Groups in Washington DC before continuing onto California.

Our first day in Washington DC was filled with a range of different briefings. Some of the more interesting observations for me were the comments from the American Farm Bureau (AFB) around the desire to foster innovation on farms, which they saw as being constrained by heavy regulatory requirements.

It was also interesting to hear that agriculture is still very influential in the policy space and that their farmer members are very closely engaged in the policy process compared to many other sectors. Accordingly they probably had a greater voice compared to farmers in other agricultural nations, where farmers make up a very small percentage of the voting public.

The importance of lobby groups was also something that stood out for me, as they appear to be far more active in the US than I observed elsewhere during the GFP.

The comments made by Matt Perdue (National Farmers Union) had a familiarity, in terms of seeing consolidation of farms and the corporatisation of farms as profitability of smaller farming units reduced.

I was also surprised by the comments that his farming members saw climate change as a big issue, and that they were individually seeing climate change affecting their farming businesses. I felt however that there was a lot of push to enable self-regulation, but not much talk around how this would be seen to be achieving the desired results.

It was also surprising to hear that internally the US agriculture sector may not be as supportive of Trump policies, especially in the trade space as is perhaps publicly portrayed.

In terms of emerging trends in Ag, there was a lot of focus on GMO and gene editing, with much commentary around how farmers saw Precision Ag as a pathway for navigating the changing regulatory environment. A highlight from the briefing by the USDA was learning about the USDA small business innovation grants program, which has been set up with the purpose of de-risking technology development by investing with businesses and then providing the government with the first right to utilise or purchase the technology, something that is being done to the tune of 2.2 billion dollars each year.

A brief visit to Capitol Hill was an opportunity to feed the inner political science graduate in me. It was an amazing place to visit, in terms of the opulence in the senate building itself, and the history that seeps from its walls.

We had a very informative briefing about the Farm Bill and its current negotiation process, it’s purpose, and the politics of trying to get bipartisan agreement to the bill, which appears to often be complicated by the fact that to get democratic support for the bill, it is not possible to decouple the food welfare (SNAP) aspects of the bill from the other farming related funding.

The value of the farm bill is around $954 billion. Nutrition is the biggest portion (75%), commodity programs receive around $7-8 billion, crop insurance $8-9 billion, and conservation $6 billion.

An interesting fact about the Farm Bill is that if bipartisan agreement is not reached, then the five year funding block reverts back to the 1940’s funding allocation, which is seen to be a motivator for all parties to reach agreement.

A visit to California was a nice change from the cold weather of the previous three weeks. Our week in California was based around the Central Valley and San Joaquin Valley areas, where there was a lot of focus on a few common issues including;

- Water

- Labour

- Increasing Regulation

We were given a good overview of the history of irrigation water in the California area, much of which has ageing infrastructure which has become less and less reliable over time due to increasing population demand on domestic water supply coupled with increasing environmental regulation, especially in terms of minimum/residual flow obligations for protection of endangered species.

This change in water reliability is driving a change to more dry tolerant species and more profitable cropping systems, including a move away from row crops to permanent crops, especially almonds, pistachios and walnuts.

In most cases the properties we visited had transitioned away from flood irrigation to micro spray or dripper spray in an effort to spread irrigation water further.

The new regulations addressing overallocation of groundwater aquifers is creating a lot of challenges for many businesses. It was interesting to learn about how the degredation of groundwater aquifers came about on the back of surface water restrictions which drove wholesale abstraction of groundwater to the point that regulation is now required to address the depletion of the water resource.

There was a lot of emphasis on the potential for groundwater aquifer recharge methods, basically involving flooding/holding water over an area and letting it infiltrate back to the aquifer.

However I was left with a few questions from a science perspective whether this approach was likely to be successful given the high evapotranspiration in the valley and the depth of the aquifers and their confined nature.

In terms of some general observations from California;

- There has been a significant shift toward permanent crops, including almonds, which are less labour intensive.

- Many producers are also trying to move towards value add processes, such as processing raw product into consumer goods. We saw some good examples of this within the Walnut and Almond sectors.

- There is a view that ‘organic’ is not likely to take off as significantly in US markets as it is too difficult to manage and customers are not prepared to pay for this, however it is likely that there will be a significant space for demonstrating animal welfare standards, and antibiotic free products.

- China trade tariff implications are a concern in California.

Mexico

Next up was a quick trip to Mexico, where we travelled to the CIMMYT Ciudad Obregon Wheat Research Centre, a 2-hour flight north of Mexico City located on the western coast of the Gulf of California.

Here we had the opportunity to learn about a large range of research happening relating to wheat as we spent the day at the research centre hearing from a range of different researchers. It was great to get an insight into the global reach of the research being undertaken at CIMMYT, and to see how they were trying to adopt new technology, including drones and manned aircraft for crop observation and management.

On the second day of our visit to Obregon, we were hosted by the Sonora Association of Agriculture, which works with its members to undertake marketing of agriculture products, group purchasing and financial credit services. The main crop grown by it’s members is durum wheat, with approximately 1 million tonnes of wheat produced in the Sonora regiona annually, making them the third largest exporter of durum wheat in the world.

A great way to finish our visit to Obregon was the opportunity to have a traditional Mexican lunch with our hosts, and for the first time since leaving home I was convinced that the steak was well worth eating!

A half day in Mexico City to finish our quick trip was an added bonus. The city of roughly 9 million people is relatively sprawled out, but there are people and cars everywhere, and the difference between the “haves” and the “have nots” is astoundingly obvious.

We were able to visit Centro Historica which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site right in the middle of the site. The square is known for its ruins, some of which date back to the Aztec era.

Brazil

The penultimate leg of our trip was Brazil, where we spent the most time during our 6 week GFP. Whilst Mexico and Brazil are seemingly close when looking at a map, the reality is it was a nine hour flight from Mexico City to Sau Paulo, followed by another couple of hours flight onto Brazillia the capital of Brazil.

The energy in the group as we embarked on the Brazil leg was high, no doubt fuelled by the excitement of our host Sally Thomson whose enthusiasm and ability to navigate Portuguese were invaluable.

For me the opportunity to learn about a New Zealand success story in Brazil first up was great. Simon Wallace was able to speak to us about his families dairy farming venture in Brazil, and how they are moving up the value chain by now not only producing their own UHT milk but also moving to other value add dairy products such as yoghurt and icecream.

The challenges that Brazil faces in terms of overcoming its political instability and images of corruption remain forefront. This was something that many of the farmers and businesses we met with emphasised was their lack of faith in the administrative systems of Brazil.

Whilst in Brasillia we had the opportunity to visit both government departments, research institutes, as well as having the opportunity to visit the Australian Embassy.

Our next stop was Cuiaba the capital city of Mato Grosso State, which is the westernmost state of Brazil. Mato Grosso State is apparently also known as “The Devil’s Armpit”, a name we had the pleasure of aquanting ourselves with as we left the air conditioned airport, and hit a wall of 38 degrees and close to 100% humidity.

In Cuiaba we were given a thorough overview of agriculture within the state, which has really only been developed within the last 30 odd years as the early agriculturalists from Southern Brazil made their way to the west. The challenges that Mato Grosso state faces include issues with transportation, distance to markets and overall infrastructure. Many farms are some 2000 kilometres by road to the nearest port.

It was of interest to learn that until the early 1990’s Brazil imported as much as 90% of its food, which is part of the reason that further development of agriculture in Mato Grosso State began.

Certainly the highlight for all of our group when we were in Mato Grosso state was the opportunity to meet with and visit some of the farming enterprise known as Bom Futuro. The success and scale of this family owned farming business, known as the worlds largest privately owned family farm is in many respects incomprehensible. This farming enterprise is only one generation old, is owned by three brothers and a brotherin-law, has over 5,000 employees and farms both crops (grain and cotton predominantly) and livestock (cattle) as well as having a fish farming enterprise.

We were privileged to have the opportunity to meet with the second generation family members, who were incredible hosts, and open to sharing their experiences in terms of agriculture and what they believe to be the future challenges of farming, one of which relates to the issue of succession, and how they as the second generation can demonstrate to the first that they are capable of continuing to be good farming custodians.

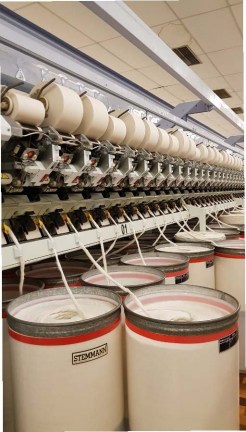

Also of interest during our time in Mato Grosso was the investment in technology that the cotton co-operative Cooper Fibre has invested in their mill, an investment made all the more expensive by large importation taxes in Brazil.

Travelling through Brazil you quickly realise that nothing is close. Our next stop was Porto Alegre in the southern state of Rio Grande Do Sul. Here we were given the opportunity to visit a factory which is processing citrus to create essential oils, as well as visiting a biogas facility which receives 6000 tonnes of waste per week and is producing about 1200 cubic metres of biomethane per day.

A last minute itinerary change meant that our group was able to take the opportunity to visit the Inguazu Falls which are located on the border between Brazil and Argentina, and at any one time can have between about 150 and 300 waterfalls depending on the water flow. Our visit here was amazing, and a once in a life time opportunity, that none of our group wanted to pass up.

Our last stop in Brazil was Sau Paulo, a city of 20 Million people on the eastern coast of Brazil. The highlight for me during our time in Sau Paulo was the opportunity to visit the Centre for Rehabilitation, Education and Nutrition. This is an educational outreach centre focused on dealing with children with nutritional challenges, including severe malnutrition and obesity. The centre is located in a large slum area of Sau Paulo, and the small number of children and families that the centre is able to reach appear to be benefiting from the work that they do.

It was incredible to be able to play with these children, and gain a deeper insight into the importance of food especially for those whom food is more of a luxury than a necessity. For many in our group, our visit here provided an opportunity to check in with the reality many people in the world face, but it was so great to be able to see a community initiative having benefits albeit to only a small number of people in need.

New Zealand

7 weeks after leaving home, I was finally on the last leg of my travels, New Zealand bound with 9 other scholars, many of whom had not previously been to New Zealand.

After an early arrival into Auckland, we were off to Hamilton, where we had the opportunity to meet with LIC and Dairy NZ at Ruakura. Whilst unfortunately we were unable to get out onto the farm itself due to the fact we had just arrived from South America. It was great to see biosecurity protocols in place as the need to protect New Zealand (and Australia) from pest and disease incursions was something that had had much debate in our group.

Those with links to the dairy industry were certainly impressed with the knowledge that was shared with us during our visit in Hamilton.

Taupo was our next destintation. We were given an amazing opportunity to gain some understanding of New Zealand Maori Agri-business with a visit to Opepe Farm Trust, which is located on the Napier -Taupo Road. Understanding the challenges that a multi-owner farming trust has to face, and the key drivers in indigenous agriculture was something that the entire group enjoyed learning about.

A few days down time in Taupo was definitely needed at this point after being on the road for so long. A highlight of this being the ability for everyone to take out some of their pent up frustrations with a round of paint ball and some golf!

Early on Sunday morning we packed our bags for a road trip to Hawkes Bay via Ngamatea Station. The beauty of Ngamatea Station is characterised by its isolation. 80,000 hectares of farm land, of which only about 50% of which is effective area. A tough farming environment in the high country tussock land. Ren Apatu our host was very open in sharing his vision for the property, and how they were looking to make ongoing changes to ensure the sustainability of the farm for the next generation.

Despite our best efforts to run out of fuel on the Gentle Annie Road, we managed to make it to Hastings for a refill of gas just in time. Our final stop was Hawkes Bay where we were very kindly hosted by 2016 scholars Sam Land and Tom Skerman. Sam had arranged for us to stay at the stunning Mangarara Eco Lodge. Here Sam shared both his experience during his Nuffield journey, but also shared the story of regenerative agriculture that is being undertaken at Mangarara Farm.

An opportunity to visit both Drumpeel Farm (cropping) and to learn about both Horticulture and Viticulture here in New Zealand was a great way to finish our GFP. The challenges that farmers are facing here in New Zealand, in terms of ongoing regulation, and challenges around the ‘social licence to operate’ gave an interesting insight into farming in a New Zealand context.

It was also great to be able to quantify the challenges that New Zealand will continue to face in the future, particularly in terms of biosecurity which is something that the Horticulture Sector in particular is very concerned about.

When I reflect on my six week GFP, I am reminded of the many similarities that agriculture has throughout the world, but at the same time the contrast in issues that agriculture faces are also significant.

Finally, something I wasn’t fully cognisant of prior to commencing the Nuffield journey is the hospitality shown towards scholars, the time people are prepared to give and the doors that have been opened.

Without the hours of organisation that go into preparing for our trip by Nuffield, but also the time given by both work and most importantly our families, this opportunity would not be possible.

Global Focus Programme – Andy Elliot 2018

Our Global Focus Programme travelled through Italy, Texas, British Columbia, Argentina and Chile. A month on from finishing my GFP, certain themes remain fixed in my mind, here’s my highlights package.

Italy – “people, travel, not food”

Italy was a real change of focus and priorities to the export orientated Netherlands. It’s been all about regional, all about local and all about celebrating what is produced.

Our first host was from the slow food movement which connects health and wellness with the function of growing and producing food locally. They believe local food should be available at the cost of production plus some reasonable return of value to farmer added. A supermarket does not allow for this to happen, its unsustainable. The value of food is not in what the brand says it is, its value is the nutrition and health proposition that it offers the consumer.

This is a country that seems to have their priorities well in truly in order. They are certainly not sprinting to keep up with the countries around them. They celebrate the food they produce, they take time to enjoy, discuss and socialise their bounty and alcohol is always consumed with food.

The younger generations are seen to be the innovators and have embraced the value of marketing and being niche. There are some extremely innovative businesses and they truly understand the value of storytelling, of the incorporation of their heritage and family tradition in the products they produce. These stories are real and inspiring, and they engage you in more than just the product, they engage you in the culture.

Italy – farm succession

Italy’s approach to farm succession is also worthy of mention. In an environment where 20% of farmers do not have succession plans and where levies are still being dished out, they have adopted a mentoring succession plan. This plan allows for older farmers to only get their modernisation subsidies if they take on a successor. The theory is that there is an abundance of farming siblings who will never inherit farms, this gives these aspiring farmers an opportunity to work with a farm owner collaboratively over a time frame to eventually take over the farm. The current farm owner gets their full subsidies, a potential successor, innovation and modernisation and the young farmer gets the opportunity to one day own a farm.

Its sounds great and if its working seems like a sensible solution to a global issue and for once I see a real benefit in subsidies, or at least in the leverage of them by regulators.

Washington DC – Slow turning ship

An emerging trends panel from some key agricultural groups fronted our questions about the agricultural industry. Interesting as you could change the country, but the first two are always up there;

- Labour was a key issue and with new systems being put in place such as the E-Verify system there is a lot of concern about how this will affect business. Immigrant labour both legal and illegal is a huge part of agriculture and farmers are concerned that this system could provide more hurdles than benefit.

- Surprisingly climate change was seen a major issue. With events occurring with increased frequency, affects were being seen through the whole farming community. Policy was one of the important drivers and barriers for change, especially in providing the right incentives for reducing emissions and the use of renewable fuels.

- There was a lot of discussion around U.S. Farm Bill, which is up for review this year. This allocates some US$956B, over a 9-year period. What was fascinating is that they were expecting no surprises with the passing of this Bill, they certainly weren’t foreseeing it being used as a political crowbar. It currently hasn’t passed, causing further uncertainty for this agricultural spend and the farming sector.

For me the one of the key take home messages from all of this is that US system is not set up for radical change. It seems to be set up for the complete opposite. The politics are one thing, but the policy and reforms are a slow-moving ship and icebergs that may appear in the form of Trade Tariffs may take a while for the US Ag Industry to manoeuvre around.

USA – Utilising new technology

As with NZ there is a lot of talk of new technologies becoming available, top of the list is gene editing. These groups discussed the importance of coalition and achieving good communications about what is occurring. Education for consumers, industry and supplier’s is crucial as well as the importance of not having technology owned by two or three large corporations.

In NZ this discussion needs to focus on facts. New gene-editing tools, either CRISPR or the slightly older TALEN, don’t insert a foreign gene into the plant to create a new trait (as typically happens with conventional GMOs) but, rather, tweak the plant’s existing DNA. It is cheaper, more powerful and more precise and is aligned to our traditional methods of selective breeding. The take home for me is that I just don’t NZ embracing the discussion fast enough.

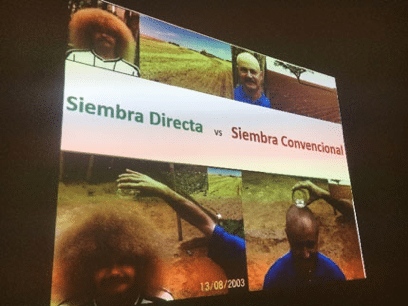

Argentina – 92% No-Till

This was a real contrast after the US and Canada. Argentina has a unique production capability, which allows three crops to be grown within a 12-month cycle. This gives farmers an advantage, but 20 years ago their soils were quickly becoming eroded and fertility was dropping.

No Till was brought in to reduce the costs of fertiliser and was then quickly adopted as they realised improvement in production and soil health. Today they are around 92% No-Till, with wheat, corn and soya dominating production. No subsidies, in fact the Govt takes around 30% of the yield of each crop. 80% of farmers lease some land on a year by year contract, this allows young consortium of farmers to enter the Industry. Agronomists are a crucial part of the farming fabric with up to 80% of farmers engaging the services of private agronomists.

Argentina – CREA

This was one of the highlights for me –CREA stands for Regional Consortia of Agricultural Experimentations. A national organisation in Argentina where there are 227 groups, with around 2000 participants. Each local group comprises of around 10 farmers, they hire an Agronomist who visits every farmer once a month.

The cool thing about these groups is that once a month one farmer hosts the other members for a day. This farmer puts up a topic for discussion. Everything is on the table, the group reviews crop records, financial returns, business structure, succession plans and accountancy. They collectively discuss the issues and topic, with honesty and intent, they rely on the collective learning of the group to be better farmers and help each other.

Regionally these groups can undertake crop experiments, often supported by third parties for example fertiliser or seed companies. The group, with their agronomist undertakes these experiments and owns the data. Nationally the organisation, although not political is involved in steering groups and advisory boards at a high level.

Could we do this in NZ? Would you open your books to others in your farming community?

We met one farmer, an oldest child whose father had passed away while he was studying at University. His local CREA group took over the management of the farm so he could continue to study. Twenty years later the son took over the full time running of the farm for the first time.

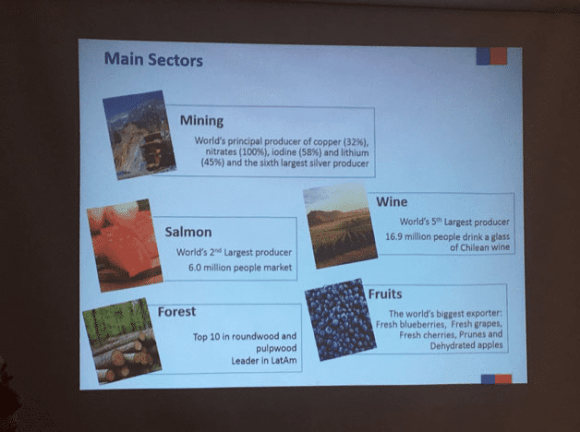

Chile – Can grow anything, quickly

With record export numbers in most horticulture categories to the US and China, Chile is cranking out the volume. If there’s money to be made they will grow it, quickly and at scale. Arriving in San Diego after Buenos Aires the first thing we all noticed was the urgency and the seriousness of the people in the street. They were on a mission and they weren’t taking their time. The economy and middle class is growing fast.

Horticulture exports from Chile is valued at $5B, the same as NZ. This surprised me given the huge volumes that Chile produces. I think NZ has invested heavily in marketing, food security and food safety and as a result gains more value in export. Zespri is the envy of other countries and is seen as the poster child of Horticulture with good reason.

I loved Chile, there is a lot of opportunity here, but instability at a political level is just around the corner. There are cultural issues too, and it appears that these are not keeping up with the rapid rate of growth and development the country is experiencing. I think that when there is expansion and growth at this level speed wobbles are inevitable, and this will impact us. Biosecurity and phytosanitary issues will become a lot more important and under increased scrutiny, and I think we need to be working a lot closer with this country.

In summary – The best little country?

Looking at NZ from across the world we are a producer of quality, we have those credentials that others respect, and being away for a while has made me realise we still have a massive advantage. However, I think we need to look to the future a bit more, I think that we need to be activity pushing the definition of what our quality stamp actually is? If it is environmental and clean and green, then let’s make it that way. Let’s go beyond what it is now and embrace regenerative farming practices, choose sustainability and frame our natural assets to be the preferred exporter of trust, food security and safety and let’s use our GMO-free status for leverage.

If the world is saying that value is not going to be in crops, animal protein or commoditised products in the future, then we should transition more of our production into differentiation or go further up the value chain into ingredients or extracts and other forms of added value. The technology is out there, we don’t have to reinvent it. We need to celebrate more of our success, sing our own praises when it comes to food safety and monitoring for export standards. What amazed me is that NZ is already competing everywhere, there is technology, there are food products and brands and investment. We don’t actually know how good we are.

Our story is authentic, but so is everybody else’s. We need to be united on what it is that is going to differentiate us in the next 5-10 years. We should not be complacent and believe that other countries cannot compete, because competition is going to increase, and we shouldn’t just be following we should be leading.

Global Focus Programme – Turi McFarlane 2018

38 days, 5 countries – the 2018 Africa Global Focus Programme in my words

The 2018 Nuffield Africa Global Focus Programme (GFP) was unrelenting and motivating to the core. This extended period of travel with 8 other international Nuffield scholars was nothing short of incredible – challenges would be laid down, preconceptions shattered and friendships forged.

After a whirlwind 8 day Contemporary Scholars Conference in The Netherlands, I set off on the Africa GFP, along with 8 other Nuffield scholars from Australia, Ireland, Scotland, Canada and New Zealand. Our journey started in the USA where we travelled through Oregon before spending three days in the capitol Washington DC. From there we dog-legged back across the Atlantic to Eastern Europe where we spent time in the Czech Republic and Ukraine. From there we finished with an extended period of travel in both Kenya and South Africa.

The USA

In the USA our journey started in Portland – a city famed for its quirky, avant-garde culture, iconic coffee shops, boutiques, farm-to-table restaurants and microbreweries. From Portland we traversed the state of Oregon visiting a wide range of farming businesses including producers and marketers of hazelnuts, oysters, wheat, beef and dairy amongst other produce.

Many of the dairy farmers we visited were doing it pretty tough in the face of an extended period of low commodity prices and it was a breath of fresh air to visit Tillamook County where the local dairy co-operative was standing out and really delivering for its farmers.

Tillamook is a high rainfall zone in Western Oregon and is home to the Tillamook County Creamery Association – a dairy co-operative particularly famous for its quality cheeses. Branding their products under the ‘Tillamook’ brand name, their members now receive payouts significantly higher than standard American commodity prices. Something that really stood out for me during our visit to the area was the Tillamook Dairy Visitor Centre. This facility is absolutely well worth visiting for anyone in the area and provides a unique space for rural and urban folks to mix and learn. The facility has been designed with the help of the farmers to give visitors an inside look, “taking you to the place where it all begins: the farm”. It was a terrific experience and something I think we could learn a lot from with regards to providing spaces for an increasingly urban New Zealand public to connect with our farming roots.

Another observation from my time in the United States was the broad sense of apprehension from within the rural sector with regards to international trade. The stereotypical upbeat and brash American was nowhere to be seen, as we met a succession of farmers, growers and industry representatives openly apprehensive about the future. Much of this centred around concerns at expected retaliation from China as a result of recent US trade policy and tariff announcements. We also heard numerous comments – largely from industry and government representatives – expressing concern at the reasoning behind the US exit from the TPPA. They expressed real concerns about the potential impact that this move would have on US trade with countries such as Japan and Vietnam, and acknowledged that countries such as Australia and New Zealand were in prime position to now take advantage.

Eastern Europe

Ukraine has long been known as the ‘breadbasket of Europe’ and now I know why. The potential for growing crops such as wheat in the Ukraine is immense. A combination of the famous black soils and significant foreign investment has seen large farming businesses (often managed by foreign nationals) thrive. Driving through this country we could travel days without seeing a fenced paddock as we passed thousands of hectares dedicated to cropping.

Africa

Most of us have heard in some form about the growing food security challenges associated with a global population expected to reach ~9.8 billion by 2050. The central role Africa has to play in this puzzle was one of the reasons I was so keen to join this particular GFP. What is the current reality and what opportunities does this present for New Zealand given that Africa is a net food importer and that more than half of the projected global population growth by 2050 is expected to occur in the continent? During our time in both Kenya and South Africa we saw two unique nations with significant agricultural potential but with quite different historical and political contexts.

Our time in Kenya was really quite inspiring. Here was a country seeing significant investment in infrastructure and a government expressing a desire to use science and technology to empower farmers as part of efforts to achieve food security and nutrition. We saw a broad range of investment into the agriculture sector, from small-scale and subsistence farming right through to large, diverse farming businesses employing hundreds of staff. The agriculture sector in Kenya looks strong and is positioning itself well for growth. The most significant challenges to this growth appear be around climate change, population growth, and environmental constraints (particularly soil health and erosion).

Our visit to South Africa was equally intriguing and offered us unique insights into a country with an incredibly complex and turbulent history. Throughout our brief time there I found myself constantly wrestling with the contradiction of incredibly entrepreneurial and successful businesses flanked by such desperate poverty. Anyone who has had their ear to the ground with South African politics over the last year will know there are some significant challenges facing the agricultural sector as part of a land reform process, part of which is proposing the confiscation of ‘white-owned’ land without compensation. Almost without exception, the farmers and growers we met expressed optimism at how this process would eventuate, but I couldn’t help but think about how this was influencing farming investment for both the medium and long term and what this would mean for the country’s economy.

So what are the opportunities for New Zealand agriculture in Africa? We need to be there, now. We need to be building our brand and presence and recognising the growing importance and potential of this region and the significant opportunities associated with trade, investment and technology transfer.

Before signing off I’d just like to express my gratitude to the many individuals and organisations who have supported me during this time. To the sponsors of the Nuffield New Zealand scholarship and my employers Ravensdown for supporting me wholeheartedly in this journey; and to my family – in particular my parents, three children and amazing wife Jessie who have all made this possible.

For more updates on my Nuffield journey as I get into my individual study, feel free to follow my blog at foodagriculture.wordpress.com and on twitter at @turi_mcfarlane.

Global Focus Programme – Solis Norton 2018

Through March and April of 2018 I partook in the Nuffield Global Focus Programme tour. With me were Turi Mcfarlane (New Zealand) and Shannon Notter, a kiwi living in Australia, from Australia Andrew Slade, James Hawkins, and Alison Larard, from Scotland Jenna Ross and from Nova Scotia in Canada Josh Olton.

Over the course of our travels we grew into a tight knit group, having never previously met before. There were many trials and tribulations overcome which gradually helped stick us together as a professional group. There were plenty of social events and hours travelling in close proximity too which stuck us together as friends. Regularly debriefing as a team on the countless discussions we had with hosts, guests, farmers and all the rest was a great help to me at least in forming my thoughts as we travelled.

While we did on occasion use some of the tools Nuffield suggested for managing the team, overwhelmingly it was the positive outlook and desire to make us work as a group that drove our transition from virtual strangers to a professionally effective team of close friends.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank them all for their time, thoughts, care, and for looking after me so well.

- Files:

GFP_Insights_Report_1_Solis_Norton2 M