Let’s sing the praises of the skills and value of our primary industries, as we do for our New Zealand sports teams.

This is the vision of farm environment consultant Rebecca Hyde, who operates under her own brand TFD Consulting Ltd, which is short for ‘The Farmer’s Daughter.’

Based in Oxford, North Canterbury, she launched her business in 2020. Much of her work week involves talking with farmers about the ever-evolving raft of regulations, a somewhat new and often complex business tier within our traditional ‘Number 8 Wire’ agricultural sector.

Over the past few years health and safety, employment and water regulations, to name a few, have become permanent features on a farmer’s business plan, directed from central government.

“A lot of farmers don’t understand all of it. It’s all come at once,” says Rebecca, the former nutrient management advisor at Ballance Agri-Nutrients and Ravensdown.

Rebecca is not shy to remind farmers that these changes are here to stay.

“The regulations will never stop, and collaboration to grapple these changes, while remembering the ‘people’ element of farming, is a must.”

Rebecca says while there is regulation involved with her business, there is also a large element of best practice.

While some farmers need more critical conversations than others, Rebecca says some don’t get why things have changed, or don’t want things to change.

“My advice is, either make the changes and I can help you, or the next person might not be so nice.”

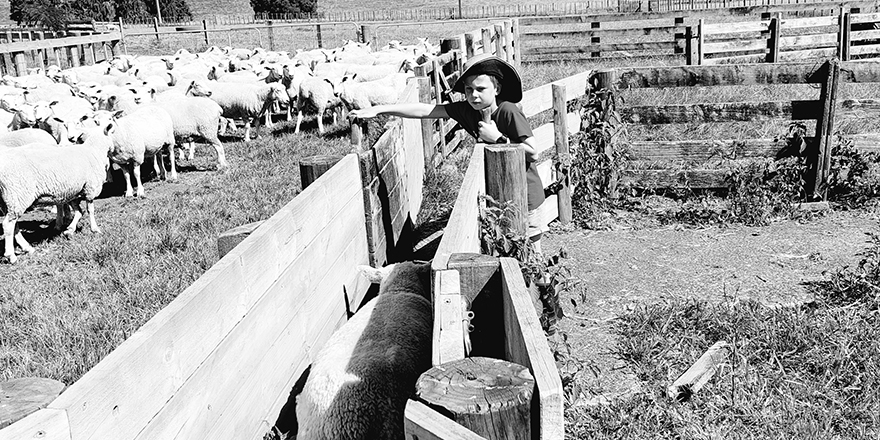

Born and raised on a sheep and beef farm in Scargill, North Canterbury, farming has always run strong through Rebecca’s veins, and she has never imagined working in any other sector.

“One thing I will always be is a farmer’s daughter. And I really feel privileged to sit down at a farmer’s table and help them now.”

Within her advisory roles, Rebecca has appreciated how in tune she has always been with farmers.

“You just get that mum and dad are trying to get the shearing done, need to get to kids’ sport, will be drafting sheep in the dust, picking up calves in the rain… You just get stuff, and farmers appreciate this.”

What appealed to Rebecca about starting her own business was embracing the challenges, and having that natural instinct of what is happening on the land.

In 2017 Rebecca was awarded a Nuffield Scholarship, which she utilised to investigate globally how collaboration works well between groups in the agricultural sector, and how well New Zealand was doing comparatively.

Her travels took her to 13 different countries including Brazil, India, America, Canada, Denmark and China.

“One of the things that came across really clearly was that most groups saw the bigger picture of working together.”

Rebecca believes New Zealand at the time was not as strong on collaboration, as there was still plenty of segregation between farming industries: dairy, arable, non-irrigation, irrigation, sheep and beef, etc.

But this has changed, and collaborative groups such as the Primary Sector Council and the development of the Red Meat Sector story with Taste Pure Nature are great initiatives that encourage conversation, ideas, and solutions for the primary sector as a whole.

Rebecca cannot emphasise enough the importance of continued collaboration and communication, and the complexity of farming that must be acknowledged.

She talks about the three layers of farming: The ground layer is the physical farm, the middle layer is the farm management system, and the third layer is the people layer.

“And that is what makes a farm unique, the combination of all of them. And farmers must work out where that sweet spot is.”

Time and time again, Rebecca has sat in front of industry ‘experts’ with her fellow farming community.

“Farmers are expected to show up and contribute, but they’re not considered experts. I think that is something that’s really been missed – that people element.

‘One thing I will always be is a farmer’s daughter. And I really feel privileged to sit down at a farmer’s table and help them now.”

Farmers have the data and the systems – they are the people living that land and system. Farmers know their capabilities, their limitations.”

Rebecca admits there is no argument that the pressures on the environment are increasing, which is human-driven. Modern day regulations have put restrictions on farmers being able to make changes on their own farm, at their own discretion. Nowadays a farm environment plan, a nutrient budget, and in some instances, a land use consent, are required.

Rebecca certainly isn’t anti regulations, which she sees as tools for raising the floor, but agrees with farmers they can be confusing.

“Farmers know the practical, and they might not need the practical changes (such as fencing off waterways), but they might just need to know the new regulations.”

Should collaboration and the ‘people’ side of farming continue to flourish, the future of the New Zealand agricultural sector is a bright one.

“Agriculture is a big business in New Zealand, and it creates business minds.”

Rebecca believes good farmers are open to different types of experts; for example dry land farmers farming for moisture and using soil moisture monitors.

She says Covid-19 has really changed how people are looking at their own health, and sees farmers as being a big part of this as food producers.

“I would like to see a future where New Zealanders are proud of what farmers do. Where someone in central Auckland is singing the praises of their New Zealand- grown food, because they are proud of what we can produce, like we are proud of our sports people.”