nuffield

Nuffield International Contemporary Scholars Conference: March 2018, Zeewolde, The Netherlands

Photo: The New Zealand Continguent in Zeewolde, Netherlands

This year 80 Nuffield scholars from 12 countries met in the Netherlands, in Zeewolde an agricultural area around 40 mins from Amsterdam. The location as part of a marina apartment complex was ideal for group dynamics as it was some distance from the closest town, but across from a holiday park which had restaurants and recreation facilities. Despite the “Beast of the East” hitting with minus temperatures, spirits and social interactions were high. (Insert the photo of venue)

The diversity of the group was expanded with invitations extended to African, Japanese and other guests as well as the Nuffield International Scholars. The 2018 scholars followed the lead of the 2017 group and did a short tour together prior to the start of the CSC visiting organisations and attending events in France and the Netherlands creating a good bond and looking at things from a NZ perspective before meeting the wider group.

The following are the reflections of the Scholars of their eight days with different messages and sharing of insights picked up.

2018 NEW ZEALAND SCHOLAR CSC REFLECTIONS

‘The Hunger Winter And The Evolution Of Subsidies’, Simon Cook

‘Strengthen Our Adaptability by Developing Collaborative Models’, Andy Elliot

‘The Future As We Know It’, Solis Norton

‘The Tiny Country That Feeds The World’, Turi McFarland

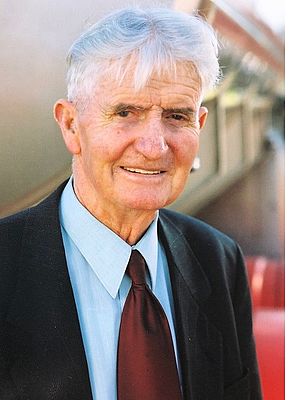

Nuffield Loses A Great Scholar

As well as a Nuffield Scholar, he was Federated Farmers National Dairy Chair, West Coast Provincial President and served for 48 years as a director on the Buller Valley, Karamea and Westland Dairy Companies.

A keen sports follower and marathon runner, Mr O’Connor was an active member of the West Coast Rural Support Trust even in his later life.

"If you’re a Coaster you’ll really appreciate the challenges there is farming near the mighty Buller River. Mr O’Connor epitomised the true West Coaster spirit through his determination and resilience to withstand the local climatic extremities. He also valiantly battled the scourge of TB in cattle and served on the RAHC – Tb Free as it is now called.

The West Coast farming community has lost one it its biggest battlers – he will be sorely missed," reflected Katie Milne, President of Federated Farmers.

West Coast dairy farmer and close friend Ian Robb, remembers Mr O’Connor’s engaging sense of humour and strong moral values.

"John had a kind, wonderful personality, he could relate to most people and the trials and tribulations they faced as farmers. He would always back the underdog and would seek out those doing it tough, and this was before the days of the Rural Support Trusts.

As his name goes, he definitely had that Irish charm. He was also a great orator and was adept at getting his point of view over in difficult conversations without offending anyone."

In his seventies, Mr O’Connor was so formidable and respected, he was still being re-elected to the Westland Dairy Companies when up against strong candidates.

"He didn’t always agree for example with the merging of the Coast’s dairy companies, but he soon got on with it, because he wanted farmers to succeed collectively," said Mr Robb.

Mr O’Connor is survived by his wife of 62 years, Del, six children and 20 grandchildren.

The Tiny Country That Feeds The World

With a much-touted reputation as the tiny country which feeds the world, The Netherlands is the world’s second largest exporter of agricultural products after the USA. The Dutch agricultural sector is diverse and supplies a quarter of the vegetables that are exported from Europe amongst a range of other produce.

During the CSC, we were privileged to hear and visit a wide range of farmers, researchers and rural professionals who emphasised several key themes over the week:

Farming land and succession

Three farmers a day leave farming in The Netherlands and with agricultural land selling for € 60-100,000 per hectare there are massive challenges for the next generation of farmers looking to own their own farm.

Feeding the world versus niche markets

With the world population expected to grow to almost 10 billion by the year 2050, we are regularly presented with the challenge of “feeding the world”. However, how does this align with obvious opportunities for us as a nation to focus on creating high value products which command a premium price in niche markets? Food security, particularly in Africa which is expected to see the most growth over this period is critical to us all, yet perhaps our greatest opportunity as a nation is to provide technical advice and assistance to improve the food self-sufficiency in developing countries?

New technologies

A number of new technologies were mentioned throughout the week as potential game changers. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing is definitely seen as having great potential, offering dramatic advances in speed, scope and scale of genetic improvement. However, the debate around GM and gene editing policy is obviously alive and well – “The CRISPR conundrum”.

We also heard about research at Waginengen University in The Netherlands which has highlighted a natural variation for photosynthesis in plants. With this knowledge they are hoping to breed crops in the future which make better use of photosynthesis – opening the possibility for much higher yields and capture of carbon dioxide.

To finish – a few interesting quotes from speakers over the week included:

“Every 20 years, the number of people depending on one farmer doubles in developed countries”.

“Climate change is here”.

“Agricultural land per capita has halved since the 1960s (worldwide)”.

“1/3 of globally produced food is wasted”.

“Lactose intolerance is more popular than skinny jeans”.