Corporate social responsibility (C.S.R.) is maturing rapidly in modern times as a way for companies to reflect the values of its customers, employees and investors. The United Nations (U.N) begun working alongside corporate organizations to encourage C.S.R. integrity in 1999 with the most ambitious development by the U.N being the 17 sustainable development goals agreed upon by 193 member states in 2015.

Much of this maturing of C.S.R has been in response to societal pressure and consumer demand. Perhaps no industry has felt the effects of this pressure more than dairy farming. Dairy is facing rising compliance as expectations of consumers and the public grow. Society is putting more emphasis on the impact of their food purchasing decisions resulting in rapid change for Aotearoa dairy farmers.

Dairy farming in Aotearoa is a unique business in that it is non-competitive at the supplier level. Farmers are not competing with their neighbour or any dairy farm, as they are all collected by a processor. Creating an environment where some low performing businesses have been able to survive that may have not in other more competitive industries, i.e. building firms; this will change. The impact potentially will have a positive effect on the standards within the industry as top-performing farmers who are more adaptable to change in compliance and ethical standards will rise.

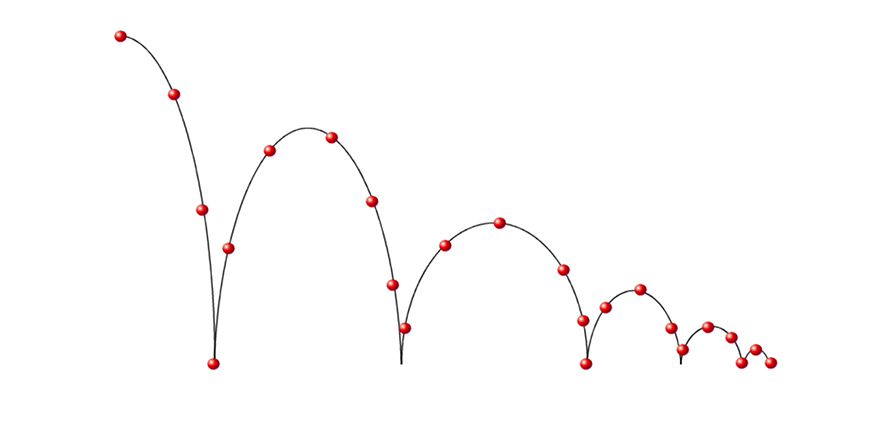

The industry must prepare to exit a large number of farmers gracefully. With current debt levels and the stagnation or loss of land asset values, many farms will not have strong financial resilience for a drop in milk price (something history would suggest inevitable) while still holistically meeting their standards in C.S.R. Additionally; others will not adapt to changes in compliance and ethical responsibilities and exit the industry due to these changes. From this will be an immense opportunity for those farmers with healthy debt to asset ratios and who can operate in the top 20% of profitability.

Carroll’s pyramid, a model for investigating a company’s C.S.R. requirements, was used to analyze the Aotearoa dairy industry’s current position. Dr Carroll, who was awarded a lifetime achievement award from Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany for services to corporate social responsibility has written a large amount of academic literature on C.S.R. Carroll broke the C.S.R. of a business into four pillars using a pyramid model. The four pillars are:

Philanthropic Responsibilities, voluntary or discretionary activities for the benefit of others or their environment. Farmers participate in wide and varied philanthropic activities; these acts are not undertaken for strategic reasons. There is potential to leverage these acts to improve perception and build on social license to operate.

Ethical Responsibilities, standards and expectations that reflect the concern for what consumers, employees and stakeholders regard as fair. Dairy farming has been slow to respond to ethical concerns of stakeholders, which has seen a loss of trust capital within relationships. As a result, in five years, positive perceptions of New Zealand dairy farming have slipped from 78% to 47% (U.M.R. Research, 2017). A social license to operate has become a vital topic in recent years regarding ethical responsibilities. In response to this, milk processors, have implemented several ethical agreements with their suppliers setting standards above and beyond legal compliance standards, to meet public and consumer pressure.

Legal Responsibilities, business is expected to comply with laws and responsibilities set by the Government; economic returns must be achieved within the framework of the law. Compliance is rising, and the cost of this is high. Top farmers will rise to the challenge, and many low performers will fall out of the industry due to increasing compliance. The increase in specific laws is a result of the loss of trust in stakeholders’ views towards dairy achieving its ethical responsibilities. Ethical trust must be rebuilt with stakeholders to reduce growing legislated compliance. The industry will be held to account of its worst producer, not its best. The bobby calf scandal (Max Towle December 6, 2015) highlights this and shows the media will portray most of the industry by the actions of a minority.

Economic Responsibilities, It is essential that a successful firm be defined as one that is consistently profitable. The average return on asset of 0.5% for 2018-19 season, with a breakeven milk price returning between a $9,000 and $48,000 per 100,000Kg of milk solids, is not a worthy reward for the effort and is unsustainable long term. Capital gain on land can no longer be anticipated, operating profit is all that can be relied on, and this is volatile due to milk price. To be resilient and last long term, farms need to target the profitability performance of the current top 20% and continually improve.

To win in the future of Corporate Social Responsibility, farmers and the industry will need to achieve the following:

- Reinvent their business constantly, the end goal may be the same, but the tools and methods are constantly evolving. Embrace change.

- Removal of farmers that risk tarnishing the industry, one farmer is a danger to the reputation and acceptance of all. Milk processors and Government must take responsibility of this. This will increase ethical approval by the public.

- Invest with the head and not the heart to be sustainable and ensure a more acceptable return on assets and manageable debt to asset ratios. Purchasing a farm must be made as if investing in a commercial building or other investment utilizing similar financial models.

- Acquire greater financial skills and drive profitability. Farmers should target to perform at the level of the current top 20% of operating profit. Action by the wider industry, including milk processors, must occur around educating farmers on profitability. If they do not, farmers will struggle to meet ethical and legal expectations of the industry. These all work in harmony.

- Understand the “why” behind compliance better, were compliance instigates from and what it enables. Conversely, the industry must explain the reasoning behind compliance clearer and more intentionally to farmers.

- Formulate successful plans and models to exit a large number of farms gracefully from the industry. Support in planning and strategic decision-making is lacking at the end of many farmers careers. Banks, milk processors and industry good organizations must take accountability to support in this.