Agriculture is the most dangerous occupation in New Zealand, the UK and Australia.

Despite the introduction of the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 and a focus on improving health and safety, the rates of fatality and harm in NZ agriculture remain stubbornly high. This has negative impacts on the sector’s productivity, profitability and sustainability. The consequences for farming families and communities are tragic.

This report explores the paradox:

Farmers care about people and each other and Their workplaces kill, hurt or harm too many people.

The report draws on semi structured interviews with nearly 50 stakeholders complimented by conversations with countless farmers, their team and family members. A review of research exploring the current state of health and safety on farm and how farmers think identifies possible root causes of the current state (what’s happening now).

Although largely invisible, assumptions and beliefs powerfully influence farmer behaviour including:

- Lack of perceived susceptibility (they don’t think they personally will get hurt)

- Risk is normalised by family and peers (everyone’s doing it)

- Risk is assumed to be a part of farm work that can’t be managed or controlled (when accidents happen they are explained as “freak” events or unpreventable)

- Risks are perceived to be common sense and people are expected to take care of their own health and safety, with some being perceived to be ‘just accident prone’.

Farmers expect themselves and their people to be super human!

The report uses the Conscious Leadership’s Fact vs Story model to explore common farmer beliefs and compare these with facts and data to identify the “stories” that prevent positive change.

Given unhelpful stories are a strong influence on behaviour it is critical that interventions address these beliefs and farmers’ “mindset”.

However, interventions have traditionally focused on “education only”. Health and safety has been pigeon holed as a compliance issue of little value to individuals or their businesses.

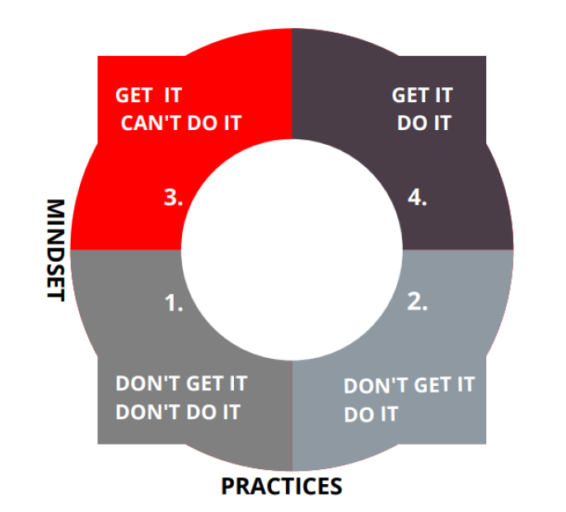

Establishing the “why” or “what’s in it for me” and the compelling benefits of good work design, is critical. The mindset/practices model shared by Fiona Ewing at the Forestry Industry Safety Council identifies the importance of establishing both the mindset and capability to support the design of good work.

There are examples of farmers in quadrant 4 (get it, do it) which demonstrate what is possible for the sector if the correct mindset and practices (capability) are established.

There are many measurable benefits of good work design which will help establish the “why” for individual farmers including:

- Higher engagement

- Lower absenteeism

- Enhanced social licence

- Better attraction and retention

- Positive return on investment

- Lower costs

- Increased productivity

Articulating these benefits may provide farmers with something they really want (better work and work environments which address some of their existing challenges).

Good work results in win:win:win outcomes: better work quality, more productive and enjoyable work environments and healthy and safe people.

Challenging pervasive stories and unhelpful beliefs requires relationships built on trust. It is important that the sector values those who bring diverse thinking and non-technical skills. Non-technical skills are identified as critical to better health and safety outcomes. Supporting farmers to develop non-technical skills will improve health and safety outcomes but also have a range of other benefits at business and sector level.

Credible, trusted “connectors” need to be available to support farmers to make change – the messenger makes a difference. To be effective these connectors need trusting relationships with those they seek to influence. Building these takes time and requires proper resourcing. It is important to take a holistic approach to the farm system that acknowledges good work design is fundamental to success and influences all aspects of the enterprise; health and safety can’t be put in a box.

Once the benefits of good work are articulated and farmers “get it” or connect emotionally with the “why”, the what and how become easier.

With the right mindset, the focus becomes lifting capability by setting up farmers up for “can do”. They need:

- The knowledge (an understanding of why, how and what to do)

- The skill (the research shows this must encompass both the technical and non-technical skills required for success). Developing skill requires practice and it is important that support is provided during this stage.

- The method – The correct method for “good” work design, specific to the farm context and focused on practical and effective outcomes. This requires an understanding of the hierarchy of controls and an emphasis on higher level (more effective) controls like elimination or minimisation, rather than the current sector wide focus on lower level and less effective controls (administrative controls or Personal Protective Equipment). It also requires collaboration and leadership to agree “what good looks like” for the sector.

- The tools – Support from up-stream duty holders (those who share responsibility for controlling workplace risks) is required to ensure farmers have access to the tools required to manage risk in their workplaces and set up for “good work” in a practical and effective way

- The resources – the money, materials and people to be successful. The closed border and current immigration settings are currently a limiting factor due to the severe people shortages in the sector.

Only if all five components of “can do” are present can farmers be expected to successfully manage work design and ensure healthy and safe outcomes for their people.

Increasing awareness of “what good looks like” is also critical to changing behaviour and social norms. This requires a cohesive sector communication strategy. All sector stakeholders need to collaborate to support the messaging which should focus on 2-3 key components.

The Health and Safety at Work Act provides significant fines and other consequences for farmers who fail to provide safe and healthy work. However, the fragmented, low surveillance farming context reduces the likelihood that these consequences will result in change. Farmers are more likely to die than be prosecuted.

Raising awareness about why, how and what should be done and increasing accountability may be more effective. Leveraging “belonging” to change social norms and make good work design an attribute of great farmers may be more successful. Farmers want to know: are my neighbours doing it?

Changing social norms requires a compelling vision for the sector. This is more likely to be successful if it addresses health and safety by stealth, given many farmers have totally disengaged with the tainted health and safety brand. Motivating farmers with a vision which connects with them on an emotional level is more likely to be successful.

Supporting change by communicating:

- through multiple channels and mediums

- using visuals and graphics (rather than text)

- through story telling to share stories of positive change and develop self efficacy (a belief that farmers have the ability required to design good work and prevent harm)

- examples of the journey taken by farmers at all stages (beginning, developing and excellence) focused on small, low/no cost changes and safe change at a pace and scale suited to individual capacity and resources

- realistic examples of positive change aligned with something farmers really want (more enjoyable, productive workplaces with fewer people headaches) is the recommended approach.

Ensuring intervention before risks become habituated or “normal” is critical and leveraging children and young people before they embed unhelpful beliefs is key. The next generation of farmers and young people are at the heart of this cultural and behavioural change. Significant change may take a generation and resourcing needs to reflect this and be independent of political cycles.