During the last two decades (1995 to 2015) the New Zealand dairy industry has undergone significant growth. Nationally, cow numbers have increased 70% from 2.9 to 5 million, the area in dairy has increased 45% from 1.2 to 1.75 million hectares and milk production has increased 129% from 8.1 billion to 18.6 billion milksolids (DairyNZ 2016).

There is significant public concern over the water quality of our streams, rivers and lakes. A number of reports indicate dairying contributes a disproportionate amount of nitrogen to waterways relative to other pastoral land uses. In areas with declining water quality it is easy to assume this is a result of increased dairying, given the overall growth. However, it is likely regional variation exists with some regions having static or declining cow numbers, in which case drawing a link between declining water quality and increased dairying may not be justified. Alternatively, water quality may not have changed in some areas where rapid growth has occurred.

The aim of this report was to present industry trends based on objective data for each region. This can be used to help develop effective regional policies and strategies for the dairy industry, including using knowledge of farm systems and farm demographics to increase effectiveness. For example, targeting a particular segment of the industry such as a certain locality or herd size. Due to time constraints it was out of scope to explore what drivers may have led to any regional changes identified.

Data were sourced from the New Zealand Dairy Statistics and the Dairy Industry Good Animal Database.

These data confirm significant changes in the New Zealand dairy industry between 1995 and 2015, which differ by region. Regions were classified into three sizes (by number of cows): large, medium and small; and into four groups by the scale and direction of the change in cow numbers: decreasing, static, slight growth and strong growth. Five regions, Taranaki, Northland, Wellington, Tasman & Nelson and Marlborough have had static cow numbers for a decade or more and some of these regions are now below their peak numbers. Auckland has fewer cows than it did in 1995. The remaining eight regions have had an increase in cow numbers, and are still growing or have been growing until recently. Waikato, Canterbury and Southland have experienced significant growth and are also large dairying regions.

The planned start of calving date has either stayed the same or moved earlier by up to 15 days, depending on region. This is likely to have resulted in increased feed demand on-farm and a shorter winter period, decreasing the time available to increase body condition. Northland had an increase in autumn calving cows in the late 1990s, as has the Waikato since 2013. The percentage of autumn calving cows was relatively constant or declined in other regions.

There has likely been an increase in feed demand on-farm since 1995 due to stocking rate, with biggest increases in stocking rate in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Canterbury has the highest average stocking rate at 3.4 cows/ha in 2015, but the area used in this report does not include the wintering areas used frequently in this region. The West Coast, Northland and Auckland have the lowest stocking rates at 2.2 to 2.3 cows/ha in 2015. The remaining regions all had stocking rates between 2.8 and 3 cows/ha in 2015, the majority of these have been relatively consistent for at least the last decade. There was a decline in the Friesian breed in herds since 1995. Overall, this means a likely decrease in liveweight per cow of between 5-15 kg/cow – thus decreasing on-farm maintenance feed demand per cow.

Increases in milk production per cow (and therefore feed demand per cow) has meant milk production also increased in regions with static cow numbers. In most cases the area in dairy declined (at least since 2003), so it would be important to determine the new land use of areas that have exited the dairy industry and drivers behind the increased milk production per cow to determine whether there has been a net increase or decrease in intensity of land use in the region. In the remaining eight regions the intensity of the dairy industry (cows/ha, milk production/cow) has increased, particularly in Canterbury, Southland and Waikato.

The key recommendations of the report were:

- Each region should be treated individually; it should not be assumed that due to the national growth in the dairy industry that this has also happened in all areas. This also applies within regions. Blanket approaches are unlikely to achieve a desired outcome effectively or efficiently. Information/packages/policy should be tailored locally to increase effectiveness.

- This study provides a strong foundation for further research, in particular, linking the regional and sub-regional changes in the dairy industry reported here with changes in water quality.

- Further research could also explore the implications of the farm system changes reported here. In particular, determining the net effect of stocking rate, breed choice, calving date and milk production per cow on on-farm feed demand.

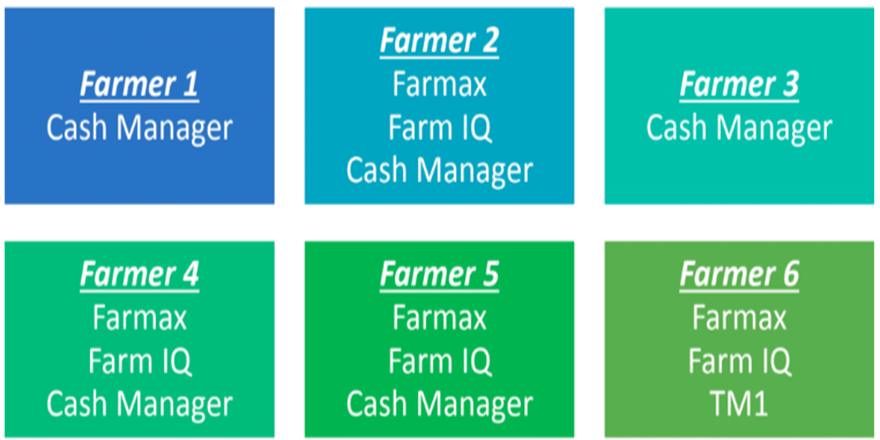

- Quality spatial data and the ability to combine different industry data sources together to generate insight is crucial. No national, farm-level, datasets that cover all aspects of the farm system exist (nor can be created by combining different data sources). Without either comprehensive or reasonably representative datasets of farm-level data, the ability to create tailored solutions locally is severely compromised. Industry organisations, such as DairyNZ, could achieve better informed sector and catchment interactions by being able to verify existing, and collecting additional spatial data. This could be aided by negotiating access to data from MPI, and milk, fertiliser and feed companies.