Executive Summary

Global food systems are experiencing unprecedented changes in the way food is produced, distributed and consumed. Food systems are highly dependent on fossil fuels, emit large quantities of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and significantly contribute to environmental problems (FAO, 2006). Agricultural farming systems particularly in New Zealand are under increasing pressure given the growing awareness of agriculture’s contribution to GHGs and deteriorating water quality.

New Zealand’s social, environmental and economic wellbeing is linked with our ability to supply the rest of the world with protein. Animal-based protein production alone accounted for over 60% of our total 2016/17 primary export revenue (Sutton et al., 2018). A temperate climate combined with advanced production systems make the NZ dairy, sheep and beef industries among the most competitive in the world. Consequently, increasing world demand for food will be a significant factor in New Zealand’s economic growth and prosperity over the next half century (Hilborn and Tellier, 2012).

Consumer concerns around the impacts of agriculture on the climate, animal welfare and water quality are increasingly influencing their purchasing decisions as they look to reduce their environmental impact including their contribution to climate change (Goldberg, 2008). This demand has led scientists to develop alternatives to animal protein from farmed animals. These alternatives have been coined “Alternative Proteins”.

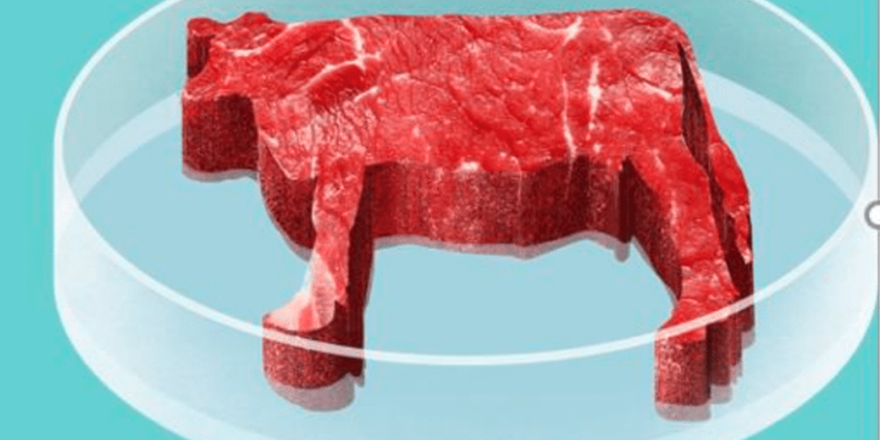

This report outlines two types of alternative proteins, these being plant based proteins and cultured meat. Plant based proteins are currently in market, whilst cultured meat is still under development. Cultured meat has the greatest potential to displace traditional farming as if successful it could address the environmental issues created from large scale intensive farming, by growing meat in a laboratory setting. However to be viable and to successfully compete against real meat, cultured meat needs to overcome a number of challenges. These include issues around public perception, cost, the ability to scale and the ability to deliver on environmental benefits.

Significant financial investment is being made into the research and development of alternative proteins and current estimates predict cultured meat will be in market within the next 5 to 10 years.

A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) was carried out as part of this report comparing the environmental impacts of cultured meat in comparison to NZ Beef. The results showed that production of 100g of cultured meat requires 0.021m3 water, 0.022m2 land and emits 0.207 kg CO2-eq Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions. In comparison to New Zealand Beef, Cultured Meat involves approximately 91% lower GHG emissions, 99% lower land use and 99% lower water use. Despite high uncertainty, it is concluded that the overall environmental impacts of cultured meat production are substantially lower than those of conventionally produced NZ beef.

Cultured meat is still in the development phase, so it is too soon to know whether cultured meat will be a marketable product, or whether the estimated environmental impacts presented here will be able to be achieved.

In order to remain profitable and sustainable in to the future, NZ agriculture needs to work on being the best that we can be in terms of our systems and practices. We need to work collaboratively both as a country and as an industry to market our products with a strong natural, grass-fed message. We need to target our products to the markets willing to pay the highest prices for these and continually look for opportunities to add further value to these products. Furthermore we should look for opportunities to diversify our farming and meat processing operations. Lastly we need to continually invest in NZ agriculture, market research and our communities in order to future proof our industry.

Given the shortfall in the current food supply predictions to feed the worlds growing population by 2050, it is anticipated that there will be room in the market for both alternative proteins and traditionally farmed meat. Nevertheless there is an increasing awareness of the impact of agriculture on the environment, on animals and on human health, which NZ Agriculture needs to stay abreast of.