By Jack Cocks and Joanne R. Stevenson.

Article is reprinted from The Journal with permission from the publisher, NZ Institute of Primary Industry Management

Farmers face adversity from multiple sources and additional challenges to other sectors of society. To date, there does not appear to be a simple high-level resilience-focused model for how farmers can be more resilient ‘personally’.

This article, which is the result of a Kellogg Rural Leadership Study on ‘How Resilient Farmers Thrive in the Face of Adversity‘, is a first step towards developing that model.

The study found there were three key strategies that facilitated farmer resilience – purpose, connection and well-being.

Adversity affects farmers from multiple sources

Like all members of society, farmers face adversity in a range of forms from health crises to financial volatility, family challenges and personal loss. Due to the nature of their business, however, farmers are more vulnerable than those in other industries to climate challenges and global market shifts. They are also often toiling at the coalface of legislative changes and can have less access to appropriate support services.

More than other industries farmers have strong identity ties to their land and business, meaning that disruptions to the farm are de facto disruptions to the farming family. They also typically live at their place of work.

The current global environment (autumn 2022) – experiencing climate, a global pandemic and a war in Eastern Europe – highlights the dynamism, volatility and interconnected global marketplace in which New Zealand farmers operate.

Developing strategies to recover quickly from adversity, or ‘building resilience’, is essential to achieving long-term success in farming. While there are a number of tools and resources available that address social-emotional resilience, there does not appear to be a simple, high-level resilience-focused model developed specifically for farmers.

Such a model could be used by farmers when facing adversity to ask themselves, ‘Are we implementing the key strategies and techniques (both as an individual and as a team of individuals) that we need to be resilient in the face of this adversity?’

More than other industries farmers have strong identity ties to their land and business, meaning that disruptions to the farm are de facto disruptions to the farming family.

Context

The lead author, Jack Cocks, an Otago high country farmer, experienced adversity from a life-threatening brain injury which saw him in a coma, suffer a cardiac arrest, a seizure and a pulmonary oedema.

On day one in hospital Jack’s family was given a prognosis that their husband, dad and son would likely be dead today. The best case scenario was that he would survive but spend the rest of his life in an institution.

He obviously did survive, and the following six years saw him undergo 15 major surgeries and spend eight months in hospital re-learning to talk, and several times re-learning to walk.

Through this experience and recovery Jack has been told that he is a resilient character. He has been asked to give several talks to farmers on his experience and how he developed resilience through adversity.

He found that giving these talks was a humbling and surprising experience for the feedback received.

However, the presentations were based on just one farmer’s thoughts and he had two questions he could not answer from them:

- The adversity he had faced, while bad, was it any worse than what many people face?

- Were his ideas on resilience applicable to all farmers, or were they just the ideas of one farmer who had faced some adversity?

Five areas of adversity

The five areas of adversity and a brief synopsis of each case are given below:

Health

Doug, who farms on the East Coast, faced severe adversity in the form of depression. This was primarily brought about through farming in what became an eight-year drought.

Natural disasters, climate and weather

Andy, who farms in Canterbury, has farmed through a succession of major weather events, snowfalls and droughts. He has a great deal of knowledge about how to farm through adversity.

Financial

Kevin and Jody, who farm in Otago, have faced a very high amount of adversity in their lives starting from before they emigrated to New Zealand.

Their major adversity in this country has been financial, in the form of a very low dairy payout in their first two seasons as 50:50 sharemilkers.

Family

Brent and Jo, who farm in Southland, experienced a number of challenges to farm succession early in their farming career. Communication and a desire to split assets evenly among all children, farming and non-farming, were the major challenges.

They have since done everything right to complete succession with Brent’s siblings and are an example for how farm succession can successfully be completed with their own children.

Personal loss

Melissa lost her husband to cancer and has since done tremendous good for her community.

It would be impossible and unfair to compare each of these stories. The level of adversity and the situations they have faced are so different that any of them would have responded differently, perhaps better, perhaps worse.

The choice of case study participants provides representation of the common sources of adversity farmers in New Zealand face and a cross-section of the likelihood of adversity from the ‘wow, that is incredible’, to ‘yes, our neighbours have been in that situation – I’ve seen it many times.’

The most remarkable story of resilience is notable for the breadth of the sources of adversity and the severity of the situation they faced.

One of the case studies is therefore an important reminder of the possibility of compounding disruptions, where adverse events seem to stack up, showing the way that resilience can be repeatedly eroded and then built back up.

Jack was able to identify some of the case study participants because they have shared their stories publicly, mobilising the power of story-telling to process their own adverse event and improve the lives of others by sharing their message.

Interviewing and examining their stories collectively revealed common themes that underpinned this diverse range of experiences.

Resilience strategies and the ‘Resilience Triangle’

Analysing the interviews revealed the common resilience strategies that the five case study participants knowingly or unknowingly put in place in their lives.

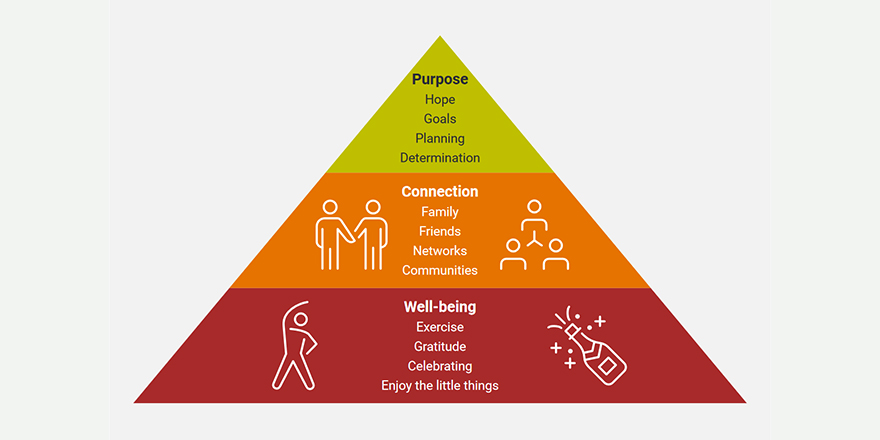

These strategies are captured in the form of a three-level triangle, the ‘Resilience Triangle’:

Purpose

This is the reason we are doing what we’re doing; the ‘direction’ of the triangle, the ‘why’.

Connection

This is the middle of the triangle; the ‘glue’ that holds it together, or the ‘who’. This is keeping connected with other people – friends, family, farming networks and local communities.

These connections are the people in our lives who buoy us up and encourage us to achieve, to rise above, and to have courage when going through adversity.

Well-being

This is the base of the triangle. It is, ‘what do I need in my life to be well’ or to be happy and content? It is the ‘foundation’ for resilience, the ‘what’.

Participants in the study placed different weighting and had different consciousness of the use of these strategies, but they are common across all five cases.

Key to the effectiveness of these resilience building strategies is the combinations of approaches across the three levels and how the participants have implemented the strategies in their lives.

For each of these strategies there were four ‘enabling techniques’ below each one that the farmers used to enable resilience at each level.

There are different enablers that underpin their sense of purpose, connection and well-being. We could identify enablers that, when missing, eroded resilience at different levels of the triangle.

The lead author cites that after brain injury induced balance issues, having sufficient stability to be able to dress standing up was a cause for celebration after having to sit on the bed to do this for so long. Enjoying the little things such as seasonal foods, a sunrise, or the first birdsong in the early spring were all cited as enablers of well-being.

Conclusions

This study was concerned with developing a theory for how resilient farmers thrive in the face of adversity. It found that the case study participants employed three strategies in their lives to be resilient:

- they lived with ‘purpose’ in that they had a clear understanding of ‘why’ they were doing what they were doing

- they were very good at keeping ‘connected’ with those people around them who would and could help them through periods of adversity

- they also understood what they needed to do to keep ‘well’ – what they needed in their lives to be happy and content.

Also, for each of these three strategies there were four enabling techniques which these farmers employed to facilitate each strategy.

Rural professionals supporting our farmers need a clear understanding of not only the causes of adversity, but some of the strategies and techniques they can use to be resilient.

The future global environment in which New Zealand farmers operate will face significant volatility, turmoil and potentially subsequent adversity.

Rural professionals supporting our farmers need a clear understanding of not only the causes of adversity, but some of the strategies and techniques they can use to be resilient. We believe this study is a first step in crystallising how resilient farmers thrive in the face of adversity.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the Kellogg Rural Leadership Programme for developing and delivering such an excellent programme. Also, to the five case study participants who have openly shared their stories of adversity and resilience, as they are remarkable and inspirational farmers.

Jack Cocks is a sheep and beef farmer in the Otago high country and previously a partner in AbacusBio, a Dunedin agribusiness and science consultancy. Dr Joanne R. Stevenson is a Principal Consultant with Resilient Organisations Ltd and farms in partnership with her husband on a North Canterbury sheep and beef property.

Corresponding author: jackcnz@icloud.com