There is a new frontier of food and farming emerging. Its emergence is in part a response to the limitations and negative impacts of our current farm systems, and in part driven by a realisation that ‘regenerative farming’ is opening up a new world of possibility. Many of our current farming systems are being ‘squeezed’ by commodity market competition and volatility, rising costs, public scrutiny and regulation, plus potentially disruptive technologies that bring significant challenges to the ongoing viability of agricultural businesses – farming is becoming increasingly complex and the future less certain. Recent KPMG Agribusiness Agendas have identified these pressures and called for New Zealand agriculture to target high end consumers, focusing on product and environmental leadership and excellence. What is perhaps less emphasised is the scale of shifts required in our farm systems if we are to truly respond to our changing reality.

This report is a call for a new and additional ‘approach’ to agricultural development and innovation in New Zealand. As I travelled with Nuffield it became increasingly clear that regenerative farming not only full of opportunities, but shifting our farm systems and practises in this direction is both a positive and necessary response to our changing reality as farmers. Regenerative farming is a broadly defined system of principles and practises focused on biodiversity, soil health, ecosystem function, carbon sequestration, improving yields, climatic resilience and health and vitality for farming communities. A key feature of these farming systems is their high demand for knowledge and creativity in designing and managing the complex biological relationships that underpin their success, as opposed to conventional systems that are more dependent on inputs for control and management. This key distinction is where our current agricultural development and innovation system falls short in its potential to support regenerative farming. Our current system focuses on a “science-driven, linear, technology transfer-oriented approach to innovation” (Turner et al. 2015) that, while perhaps suited to more homogenous and input-oriented conventional farm systems, does not align well with the more holistic and high risk innovation demands of regenerative farming (that also offers less opportunities for agribusinesses).

The ‘approach’ to support the innovation of regenerative farming systems and practises needs to move beyond old dichotomies between ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ drivers of change, towards community-centric approaches guided by the knowledge, experience and creativity of farmers and rural communities, with the support of other actors (ie. government, policy, research, relevant businesses and organisations etc). Farmer and practitioner experiences of making or 3 supporting shifts towards regenerative farming, around the world, have formed the basis for the conclusions of this report. Community-centric approaches were observed to facilitate diverse participation and place equal value on local and external expertise, where everyone ‘meets as equals’ in a shared commitment to achieving community goals. In this manner, the diverse interests of communities and society can be acknowledged and incorporated into decision- making and action, with the potential to reconcile apparent conflicts within and between rural communities and wider society.

A community-centric approach to regenerative farming innovation is also a principle-led and prototyping approach. A principle-led approach is a shift way from ‘recipe’ farm systems that are often inappropriately applied, towards a focus on translating farming principles into the diverse contexts created by land, climate and farmer skills and aspirations. A prototyping approach tests possible solutions to complex settings with a fast-fail methodology, representing a new approach to learning that focuses on diverse teams, innovation and agile testing, guided by practitioners such as Otto Scharmer and Zaid Hassan. A community-centric approach engages actors from across the system on challenges at a range of scales, such as water quality management in a catchment or rural employment/livelihoods, to challenges on individual farms (ie. what trees to plant where) that may or may not be shared by other farmers. It recognises the inherent connectedness between individual and collection actions, utilising diverse participation and commitment to understand complex settings and develop solutions that are beyond the capacity of any individual.

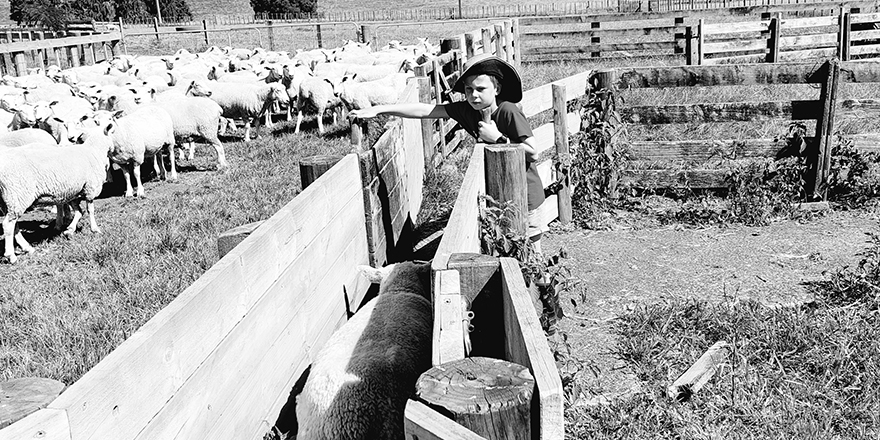

Mangarara Station, where I now live and work, is committed to a regenerative farming vision and is confronted every day with the challenge (and excitement) of working towards it. We hope to build mutually beneficial relationships with many different people, from local farmers and community members, organisations, to regional and national policymakers, researchers, sector organisations and NGOs, entrepreneurs and businesses, software developers and generally any creative person who sees opportunities here to support what we are trying to achieve. There is a huge amount that we don’t know, and therefore we must experiment based on existing knowledge, intuition and creative thought about what might be possible. It is essential that regenerative farming innovation is supported by the institutions and organisations whose mandates align with the potential value regenerative farming can generate. The opportunity for New Zealand (and other countries) is to collectively build more diverse, integrated and resilient landscapes, economies and communities that contribute positively to the future we want to create.

Keywords for Search: Sam Lang